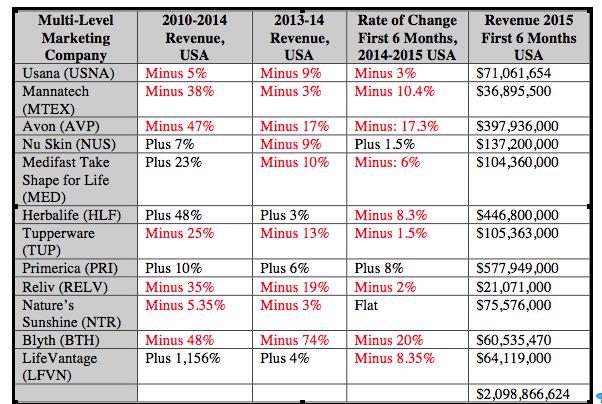

Mid-Year Data Reaffirms Saturation For Publicly-Traded 'MLM's (by Robert FitzPatrick):

| Robert FitzPatrick |

Summary

The FTC prosecution of the MLM, Vemma, has added fuel to analyses of MLM and legal questions extending to Herbalife, but leaves untouched the basic question, "Are MLMs unsustainable enterprises?".

Macro-analysis of MLM structure, pay plans, practices, and "closed markets" indicate inherent unsustainability. Analysis has been obscured by attentions on participants, not the enterprises.

Latest USA revenue data, added to a report on five years of data and analysis, of 12 publicly traded MLMs show the face of saturation and demonstrate inherent unsustainability.

Primerica data stands out as an apparent exception. Analysis shows its evangelistic recruiting does not alter the saturation scenario. The Dept. of Labor may also blow MLM-Primerica's "financial industry" cover.

The recent successful FTC prosecution of the scheme, "Vemma," revealed, once again, that pyramid schemes operating as "multi-level marketing" - MLM - are scamming vast numbers across the land. Vemma was fleecing 200,000 when the FTC finally stopped it, but many times that many during its 10-year rampage.

The Vemma prosecution has, also once again, demonstrated that consumers, least of all students, cannot tell the difference between an unsustainable pyramid fraud of this type and what the FTC calls "legitimate" MLM. The Herbalife (NYSE:HLF) controversy serves as case in point. The prosecution also confirmed - again - that while millions are lured by MLMs' "income opportunity" solicitations, statistically, virtually none that joins earns a penny. Vemma's "disclosure" of income mirrored most other MLMs, such as Herbalife's, in revealing near total loss rates.

But while the Vemma prosecution focuses brief attention on the fate of consumer investors in MLM, the most basic question about "multi-level marketing" enterprises remains unexamined by Wall Street, the media, and, most amazingly, the FTC. This question is whether the "MLM" enterprises, as they are universally designed and operate, are inherently unsustainable. If they are unsustainable, then the question of MLM illegality as "unfair and deceptive" would have a foundation for more useful and consistent law enforcement and end the absurd one (smaller MLM)-at-a-time prosecution policy at the FTC.

The Mystery of Sustainability

Sustainability for MLM enterprises is distinct from, but obviously related to, sustainability of MLM "distributorships." The capacity of millions of recruits to find the necessary tens of millions more who need to find hundreds of millions, etc., in order to build profitable "downlines" would seem to be easily calculated with exponential factoring. Yet, a seemingly straightforward math analysis has been converted into a metaphysical mystery involving unknowable and immeasurable personal analysis of the participants' inner motives, identities and roles, more complex than a Russian novel. Individuals that failed to find new recruits are suddenly assigned new parts in the drama as "customers." Middle-man wholesale pricing is said to be paid by "end-users." Distributors earn money by "selling to themselves." The inner motives of those signing MLM sales contracts are said to supersede their legal, contractual status. Were they only interested in a "discount", never an income? Just wanted to socialize? Did they love the product so much they wanted to be a "member" and happily paid the extra costs? Did those that failed and quit, just not work hard enough, and so on. Years of research are said to be necessary for determining whether a consumer has been swindled. Bring in the PhDs, consultants, and lawyers. Meanwhile, let the main MLM show go on!

Enterprise Sustainability

This essay and analysis probe the more discernible, worldly factors of MLMenterprise sustainability and saturation that prevents the enterprise itself from further expansion (in plain language, the MLM enterprise can't find enough new recruits). It offers hard data for the first six months of 2015, compared to the same period a year ago, as an update to a larger earlier report.

The fact that hard data are even required shows how "sustainability", even of MLM enterprises, deflects analysis, almost as if regulators and investorsdon't want to know. It was not always like this. In a bygone era, before the Amway case of 1979 and the subsequent FTC see-no-evil policy toward MLM, regulators saw endless chain selling schemes based on the "unlimited" income promise as dangerous frauds, capable of scamming millions and poisoning the legitimate direct selling industry. Somehow, back then, regulators were able to quickly grasp that any enterprises based on an "endless sales chain" is inherently unsustainable since they would require "infinite" expansion to fulfill their promise to all. Full stop. Prosecutions ensued. Complex analysis was not required.

Also without need of data, others have pointed out an even simpler characteristic of unsustainable pyramid selling enterprises - "closed markets." Unless the people on the chain are, in fact, earning profits from sales to those outside the chain, and do not require recruiting to extend the chain - then the funding of the MLM rewards has to be mostly internal. If there is minimal and unprofitable volumes of retailing (or almost none at all), per salesperson, then the profit opportunity existentially depends upon funds gained from the addition of others onto the chain, and inside that "closed market." In that case, no matter how large the chain grows, it cannot possibly do anything but move money around inside itself, among its own members who are themselves the source of the rewards they are all seeking. If some are profitable, it must be at the expense of the others. This is what writer and activist David Brear has termed a "closed market swindle" and why MLM's recruiting-based income promise is sometimes called a "fairy tale."

Twelve companies of the MLM type that employ the endless chain model are publicly traded (and they are the only non-regulated, publicly traded companies that do). The shares of these companies, aggregately, are valued at nearly $20 billion, not chump change even by Wall Street standards. On Main Street, their footprint has become enormous and ubiquitous. In 2014, just these 12 MLMs pulled in nearly $4 billion from close to 2 million consumer-investors in the USA, where all of the enterprises started and are operationally based. There are, reportedly, 1388 other MLMs operating in the USA!

Wall Street Resistance, Avoidance and Profit-Taking

If MLMs are unsustainable, designed to end in tears for those millions who partake in their alluring income promise, Wall Street is clearly complicit. If the MLMs' "unlimited" income proposition is only an addictive and hallucinogenic (financial) drug bought and sold on Main Street at epidemic levels, Wall Street is Walter White.

When bothersome concerns about massive consumer losses or illegality come up periodically on Wall Street, they are inevitably swept away, as will likely happen in this Vemma episode, by the fable of MLM "growth", dramatically illustrated at MLM "investor presentations" and appearing to show a vast market that, no matter how many years the MLM has operated or how many other MLMs are involved, has still barely been developed.

The colorful graphs and "surveys" are bolstered by exciting news releases from one MLM or another claiming "explosive" revenue increases, sometimes of 500%, 1,000%, and promises of "becoming the next Apple Computer." And these are supported with "data" from the Direct Selling Association about millions of invisible "direct sellers" earning sustainable profits from "retailing." A new narrative has millions clamoring for "discounts" of unadvertised MLM commodities, with no interest at all in the attached income opportunity, despite its claim to be the "greatest business in the world" - another indicator of why MLM is sometimes referred to as a "fairy tale."

The veracity of the graphs, the overview, the data, or the claims of retailing and discount shopping are seldom questioned by Wall Street analysts because, whatever they are, MLMs have provided remarkable capital gains opportunities (some of them even pay dividends). Few analysts look any further for customers or any data on the state of the "distribution chain" or the underlying business model or what the MLM enterprises' future might be. Spurts of spectacular revenue increases, volatile share prices and stock buy-backs have made MLMs darlings of Wall Street.

Bothersome Realities

History offers reminders of mass delusions about unsustainable enterprises. Bubbles and manias, ranging from tulip bulbs to dotcoms to sub-prime mortgages, have looked in their time like financial miracles. Their duration is often brief but some go on for many years. Think Enron and Madoff.

Analogously, if MLM enterprises are just strip-mining a finite and depleting resource of hope-filled and uninformed consumers with a pie-in-the-sky fairy tale, and if infinite geographic expansion on a finite globe is the requirement for MLM solvency, then MLM "growth" is merely a Ponzi chimera, and a saturation deadline is looming or has already been reached.

Though due diligence would seem to dictate it, Wall Street houses have still not examined the basic questions of MLM that are normally required of fiduciaries:

- Is MLM's available market of prospects - people who have not already lost in MLM and quit or who do not yet know of its historical performance for consumers - diminishing? How could it be responsible to invest in any MLM without knowing this?

- What is the impact on existing MLMs of all these new ones coming on line?

- What is the MLM market and what is its size? Could it be possible there are analysts recommending these stocks who cannot answer even this basic market question?

Persistent Questions

Prompted by questions from a series of inquisitive Wall Street analysts who dared to probe MLM's future, I made a study of 12 publicly-traded companies, compiling and comparing data over the last five years, 2010-2014 in the USA, MLM's home territory, to determine if revenue and recruiting data indicate saturation.

The analysts' skeptical inquiry was motivated by three inter-related, structural elements of the MLM model that, even without examining data, point toward saturation:

- Demographics, by needing to replace virtually their entire sales and customer bases every few years, creating a recruiting challenge of epic proportions, each year.

- Negative information from word of mouth reports by the massive numbers of disappointed former participants, (this is combated with an intense blame-the-victim message by MLMs.)

- The continuous and accelerating influx of new MLM enterprises that operate essentially as clones of existing ones, which dilute whatever market remains. New MLMs are also endemically produced within MLMs as upper level recruiters inevitably realize the only way to get to the top is to start there, that is, to join or found a new MLM. This spawning force is further facilitated by clone-like similarity of all MLMs, requiring no learning curve, enabling apostates to seamless transfer or create new start-ups and to bring large "downlines" with them.

Findings and Updates

- The data from the 5-year analysis, 2010 through 2014 indicate that the publicly traded MLM companies, in the geography where they should be strongest, the USA, are declining in revenue and recruiting. New, updated data presented here in this essay for the first six months of 2015 continue the analysis. The data for this time period affirm the overall pattern found in the longer term report.

- Older MLMs, best illustrated by Avon, are in long term decline, and others, like Herbalife and Usana (NYSE:USNA), after dramatic "pops" of growth, are dropping.

- Newer MLMs show the "pop and drop" pattern in shorter time frames and in more dramatic swings.

The full report delves deeply into the root causes of MLM's economic performance and its fate of saturation. The resulting study report is described in more detail HERE.

- Of the 12 companies examined, 10 experienced revenue declines or flat revenue in first half of 2015 over the same time period a year ago.

- Overall drop in revenue among all 12 was $115 million in the 6 month period, measured year to year, factoring in a $40.4 million gain by just one of the 12 companies.

- A majority of the companies have shown net declines in the four year time frame of the study, the last year of the report, 2014, measured against 2013, and the latest data on the first six months of 2015 measured against the same time in 2014.

- The one company that shows significant increase in revenue is still reflective of longer term decline with revenue today less than what it reported six years ago in the USA.

The Fact of MLM Saturation

To understand the meaning of MLM saturation requires first determining that the decline of revenue of the USA of the leading MLMs is indeed saturation-driven. The fact that saturation is responsible for the prevailing revenue decline, which is already indicated by consumer attrition and loss rates, the MLM business model, documented practices and policies and recruiting mandate built into MLM pay plans and incentives, is established by eliminating other possible market factors that are typical in business decline.

Conventional causes of decline would include product or technological obsolescence, loss of brand equity, customer disloyalty, poor management or superior performance, competitively lower pricing or more popular brand appeal by competitors. None of these applies in MLM. New companies show nothing new in product types, pricing or marketing. Customer disloyalty is irrelevant given 50-80% churn rates that are universal under normal conditions for all MLMs. Product pricing is irrelevant since no MLM has ever marketed its goods on a price basis. MLM goods are often double or triple in price to similar goods in stores or online. MLMs do not develop popular consumer brand names that stimulate product demand. (if they did, they would be in stores) None engages in significant product advertising.

MLM products are "pushed" by distributor incentives. Yet, even in "distributor marketing" no factors can be discerned to distinguish one MLM from another or to account for recent declines. MLM pay plans are famously complex, but all amount the same thing. All are based on size and structure of "downline" recruiting. Over half of all rewards always wind up in the hands of the top 1% on the sales chain at all times, and all experience and are based upon similar patterns of "churn" or "breakage."

The other conventional and common cause of revenue decline is a general economic decline. But the declines recorded in this study are during a period of economic recovery and growth in sales of the products that MLMs offer.

For some MLMs, decline has been dramatic and is continuing, though more slowly. Others are just starting their "drop." Pirating of downlines and more intense recruiting campaigns, factors which themselves are not sustainable, account for some reductions in decline rates. Yet, the overall pattern, based on numbers is clear. The publicly-traded MLMs, overall, are not "growing" in the USA market. The heydays are over.

Beyond Numbers, to Legal Significance of MLM Saturation

Saturation in MLM is not a marketing issue but an existential challenge to MLM legitimacy or legality. Data showing incapacity to continue expansion render the MLM value proposition null and void. If the enterprise itself cannot expand due to market saturation, its fundamental claim to offer an income opportunity to all new recruits - that requires enterprise expansion - is plainly false. It is a promise that cannot be fulfilled. Continued propagation of the invalid proposition means calculated, knowing deception.

Sustainable businesses can and do offer valid income opportunities as they scale down. Growth is sought but not existentially required for them to deliver value to customers and income to salespeople. Goods and services are still delivered at fair value, often better value. But, when growth is existentially required in the value proposition, as it is in MLM for the latest consumer-investors to be profitable, then inability of the enterprise to grow due to saturation pulls back the curtain on the unsustainable nature of the enterprise and the deception of the value proposition.

In a Ponzi, inability to find gullible new investors (saturation) triggers immediate collapse as existing investors become aware. Unsustainability and illegality are laid bare. But in a pyramid, the tipping point where not enough new investors can be recruited to offset losers does not cause immediate collapse. Recruiter-investors at the top as well as company owners are still able to gain significant rewards but only as long as many new investors are unaware of the saturation condition and can still be recruited. The scenario is not collapse but continued and accelerated decline, continued losses for consumer-investors and, for shareholders, doomed investment. Scamming becomes just looting.

Rapid contraction or bankruptcy of a pyramid that is in saturation would be triggered only if there were broad public awareness, requiring significant media exposure, or by general awareness of investors, resulting in a stock sell off, or, the least likely scenario, by an FTC law enforcement action.

If not collapse, saturation does trigger greater volatility with more aggressive pirating of top gun recruiters, intensified recruiting, more outrageous "unlimited income" claims, and more new MLM startups, accelerating the declines of the older ones.

The Illusion of Sustainability by Constant Expansion

For the last three decades MLMs have increased their reach and scale, appearing to show viability of the enterprises, if not the consumer investors, and enormous profits to owners, including some Wall Street investors.

Churning 50-80% a year of consumer-investors in their wake, and revealing in disclosures that in a one-year time frame only 1% are ever profitable, the MLM enterprises have successfully obscured the reality of looming saturation, by adding geography. Now, some of the largest MLMs - Amway, Nu Skin (NYSE:NUS), Usana, Herbalife - depend entirely on expansion in China, MLM's final frontier. Net gains obtained by geographic expansion also deceptively bolster recruiting in existing territories by appearing to show continued opportunity to those who don't know about the exhausted recruiting conditions locally.

The Appearance of a Primerica Anomaly

An analysis that cites data cannot avoid accounting for what appears to be one anomaly to the data pattern. Primerica (NYSE:PRI) reported a 10% gain in the 2010-14 period and significant growth in the one-year time frame of 2013-14 and first six months of 2015 over the same period a year before. Primerica only sells and recruits in the USA and Canada. It is instructive, then, to look more closely at Primerica.

Slightly longer term data show that Primerica is not anomalous to the market saturation demonstrated among all its publicly-traded MLM peers. Primerica's revenue for the first six months of 2015 is below what it reportedsix years ago for the same time period.

As for the possibility of its business model being more product-based than recruiting-based, making it fundamentally different from its MLM peers, in fact, the company data on attrition and recruiting indicate that Primerica iseven more recruitment-based than its peers are.

In its SEC filings, Primerica documents exactly how many sales reps it enrolls each quarter, how many ultimately become newly licensed and the per capita sales of new life insurance policies by the entire licensed force. The correlates of Primerica's never-ending recruiting requirements are obvious in the data:

- From 2008 through mid 2015, Primerica reported that it had recruited an astounding 1.6 million new people in North America to become licensed representatives,

- At the end of that period, the company reported that just over 100,000 were actually licensed, and 18% of them had been signed up just in the last six months. So, each year, more than a third of the entire licensed sales force is brand new. In three years, the vast majority of the whole force has quit.

- The average number of licensed sales reps for the first six months of 2015 is less than it was for the year of 2009. In other words, as many had quit as had been recruited, more than a million and a half.

- During this first six months of 2015, recruiting increased 16% over that time period a year ago. This increased recruiting produced an 8% gain in licensed sales people from a year before. The 16% gain in recruiting, which produced the 8% increase in licensees, in turn, produced the 8% revenue increase.

General market trends in term-life insurance and IRA accounts, Primerica's main products, cannot account for Primerica's recent growth as a MLM, as there has been no spike in those financial product markets. Finally, product differentiation also cannot be cited. The specific financial products offered by Primerica are indistinguishable if not inferior to others on the market.

Based on data and analysis, it can be reasonably concluded, therefore, that Primerica's recent revenue growth, in contrast to its peers' decline, is just based upon greater success at recruiting MLM prospects with its own version of the classic MLM "unlimited" income promise. Why or how would Primerica be better at recruiting MLM prospects in the last few years?

Recruiting Bolstered by Financial Products Identity

It should first be noted that recruiting itself is a revenue generator for Primerica. Each new recruit pays a fee of about $100 just to sign up and may also pay $25 a month for Primerica Online, a support and training portal, among other costs and charges. All recruits - numbering in the hundreds of thousands annually - are also primo candidates themselves to purchase Primerica's life insurance or IRA products, whether or not they ever get licensed. You can't sell what you yourself would not also buy, right?

Even more important, Primerica's recruiting success highlights the crucial and central role of the underlying MLM value proposition. This proposition for earning "extraordinary income" is purely financial, making MLMs financialenterprises at their core. However, officially, MLMs claim to be "direct selling" businesses, not pure purveyors of an income scheme. They claim to be characterized by their various consumer goods. In this identity, they must downplay or camouflage, for regulatory purposes, the naked lure of "unlimited income" offer that is attached to buying the goods and involves recruiting other participants, ad infinitum.

The "direct selling" identity and the legally necessary focus on a commodity product enables Herbalife, for example, to argue that the millions of recruits who earn nothing and drop out were actually just "customers" who never even wanted to gain income. It was all about the "product." The recruiting event was really just a retail sales transaction, regardless of the "wholesale" price and that seller and buyer were both inside the sales channel as "distributors."

Whereas the income propositions of the other MLMs are obscured, Primerica's is highlighted. All its recruits are unabashedly seeking income as licensed sellers, and there is no need or usefulness to hide this fact. In its recruiting program, Primerica can laser in on the desperate needs and desires of consumers for income, promising them the possibility of income that can "change their lives." And, because Primerica's "products" are themselves financial, IRAs and life insurance, Primerica's income promise may appear more valid and attainable. This is in contrast to other MLMs' income promises that are obscured in the first place and associated with "pills, potions and lotions" touted as weight loss panaceas, cancer cures and fountains of youth. In the recruiting world, based on appealing to a need for income, Primerica clearly has advantages.

Heavenly Fervor and Blinding Light

Assessing its recruiting campaign, since its spinoff from Citigroup in 2010, Primerica appears infused with evangelical fervor, promising what sounds like eternal salvation. In the blinding light of this mythic rhetoric, new recruits may never notice the documented quitting and loss rates or the absurdly low per capita sales rates among Primerica's disciples. It may also obscure the mundane reality of having to sell run-of-the-mill life insurance and the impossible mandate of recruiting.

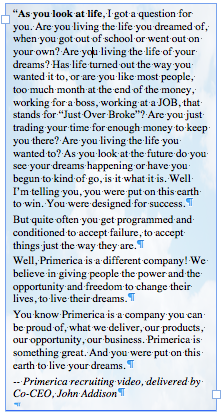

Put on this Earth to Win!

While the scale of Primerica's recruiting challenge is of biblical proportions - roughly a quarter million new recruits a year to sustain current growth - its redemptive recruiting pitch may reveal more about its recruiting increases. (Read Primerica Director and Chairman of Primerica Distribution, John Addison's sermon-like appeal on this page, but better to listen to it to grasp Primerica's recruiting message.)

roughly a quarter million new recruits a year to sustain current growth - its redemptive recruiting pitch may reveal more about its recruiting increases. (Read Primerica Director and Chairman of Primerica Distribution, John Addison's sermon-like appeal on this page, but better to listen to it to grasp Primerica's recruiting message.)

roughly a quarter million new recruits a year to sustain current growth - its redemptive recruiting pitch may reveal more about its recruiting increases. (Read Primerica Director and Chairman of Primerica Distribution, John Addison's sermon-like appeal on this page, but better to listen to it to grasp Primerica's recruiting message.)

roughly a quarter million new recruits a year to sustain current growth - its redemptive recruiting pitch may reveal more about its recruiting increases. (Read Primerica Director and Chairman of Primerica Distribution, John Addison's sermon-like appeal on this page, but better to listen to it to grasp Primerica's recruiting message.)

The spiritual, rather than factual nature of the solicitation is starkly revealed in the hard data on Primerica's extraordinary "churn/failure" rate among the hope-instilled recruits and the absurdly low pay it actually delivers on average.Primerica has disclosed and reported in its 2013 10K:

- About 85% of all recruits, after paying initial and, for some, monthly and other charges of hundreds of dollars, never get licensed and therefore earn zero.

- The average annual income of Primerica's licensed sales reps in 2013 was $5,614 before expenses. Low as it is, this "average" is heavily skewedupwards by a "mean," not a median, calculation. It includes the small group of top recruiters' high incomes; discloses nothing on how total payout is allocated to each level; omits all costs.

- During that year, 186,251 hopefuls were inducted. From this group, just 34,155 went on to become new licensees.

- The average number of new policies sold by Primerica's ever-churning force of about 95,000 licensed sales reps per year was less than three, resulting no doubt, in the massive attrition that renews the recruiting mandate. Primerica provides no data on how many of its insurance policies and IRA accounts are sold to the recruits themselves.

Inescapable Identity, Unavoidable Destiny

Primerica's anomalous success at "income opportunity" recruiting is aided by a unique aura of legitimacy based on selling sophisticated financial products. Identification with these financial products, especially to vulnerable young recruits seeking financial security, appears to lift Primerica out of a fringe and controversial MLM identity to the mainstream "financial services."

Yet, Primerica now faces a special problem related to that assumed identity. The United States Department of Labor may impose new rules on Primerica that would define its salespeople as "fiduciaries" if they are selling IRA accounts. This could be devastating to Primerica, forcing it to greatly increase training costs or even to move away from IRA accounts where the seller may be held accountable for their claims and promises under new rules.

In its latest 10Q, Primerica reported, "On April 14, 2015, the Department of Labor ("DOL") published a proposed regulation ("the DOL Proposed Rule"), which would more broadly define the circumstances under which a person or entity may be considered a fiduciary … involving assets in qualified accounts, including individual retirement accounts ("IRAs")… Such restructuring could materially impact our qualified plan business… During the year ended December 31, 2014, product sales of assets held in U.S. qualified retirement plans accounted for approximately 57% of total investment and savings product sales… we are unable to quantify the impact, if any, on our business, financial position or results of operations.

Translated into MLM terms, the DOL may be asking whether Primerica is really in the financial products business or not. Are Primerica's MLM sales people - who are rewarded not just to sell financial products but also, effectively, to recruit, with a third of them licensed less than a year and an attrition rate of nearly 100% in several years, and who on average earn almost no net income themselves - qualified and responsible to sell consumers financial services with life-long consequences?

Selling life insurance is a sustainable business. However, Primerica's business model and practices, establish its true identity as MLM, which data and analysis indicate is not sustainable. Primerica's annual solvency requires recruiting almost a quarter million new salespeople every year, with a historical wash-out rate of 85% in the first year and average annual income of about $6,000 a year for the licensed sales force. Its training, marketing and reward programs cannot focus only on sales since the recruits, as the Primerica 10Q claims, "self-generate" hundreds of thousands more of their kind, and on average, they sell less than three insurance policies a year. Primerica's very solvency depends, first and foremost, on getting its "salespeople" to be recruiters. It helps also that the mission itself generates millions in revenue for the enterprise from sign-up fees and other charges to the raw recruits.

Primerica's recent data appear to stand out, but a closer look reveals no anomaly. As it cannot escape its true identity as a recruitment-driven MLM, it cannot evade the destiny of a time-bomb of saturation shared by all its publicly-traded MLM peers.

Robert FitzPatrick (copyright 2015)