All of a sudden, the RICO Act is all over the media.

The Racketeer Influenced Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act (enacted by section 901 [a.] of the Organized Crime Control Act) is a United States federal law which (in theory) provides extended criminal penalties for, and powerful civil remedies against, the leaders and agents of ongoing criminal organizations and their de facto associate enterprises.

In the early 1960s, after Robert Kennedy was appointed Attorney General, the US Dept. of Justice was given a significant role with a co-ordinated national ‘Strike Force,’ established under the direction of the Inspector General of the US Dept. of Labor. This new initiative was the product of an overt, joint congressional policy to hold the leaders of major organized crime groups to account, as well as dismantle their webs of corrupt political figures, judges, attorneys, trade union officials, senior law enforcement agents, etc.

Even though he never faced criminal prosecution, the long-time Director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, is now known to have been under the influence of racketeers. He was certainly being bribed and probably blackmailed. Despite a growing mountain of conclusive evidence, for decades,

Tellingly, another full decade was to elapse before an elderly and insignificant ‘Mafia’ decoy 'boss', Frank Tieri (who had previously pretended to be an employee of a sportswear manufacturer), was actually convicted under RICO. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Tieri_(mobster). However, RICO legislators had access to a lot of key inside information, some of which had been supplied by 'Mafia' apostates like Joe Valachi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Valachi:

- Although, Sicilian 'cults of thieves' did not have formal names, their adherents became commonly-referred to as ‘Mafiosi’ (those who boast and swagger), whilst the gangs were known as ‘Mafia.'

- Soon, within the densely-populated Italian enclaves, ‘Mafiosi’ were employing all their familiar, brutal tactics to establish the widespread belief that if you didn't keep paying them for salvation, you were doomed. The sustainable racket euphemistically-known as ‘selling protection/insurance,’ remained the base activity, but other crimes included trafficking in illegal immigrants.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/US_Senate_Select_Committee_on_Improper_Activities_in_Labor_or_Management_Field .

- The 'Mafia' bosses were still able to sustain their wider activities by the enforcement of existing, arbitrary contracts and codes (secrecy, denunciation, confession, justice, punishment, etc.) within their ‘Families,’ and by their use of intimidation, and/or the infiltration of traditional culture, and/or corruption, and/or intelligence gathering, and/or blackmail, and/or extortion, and/or violence, and/or assassination, etc. to repress any internal or external dissent.

- Although the Italian American 'Mafia' was positively identified as a real phenomenon (referred to by its initiates as, 'Cosa Nostra' or 'Our Thing'), and various isolated 'Mafiosi, and their corrupt contacts, were imprisoned during the 1960s for individual crimes, the organization remained effectively above the law. In reality, what its bosses were doing (i.e. running an axis of secretive, and abusive, totalitarian States in microcosm, within a democracy), was, by its very nature, designed to keep them beyond the reach of the law.

The above, was essentially the catastrophic situation that faced US federal legislators at the end of the 1960s. In reality, the law they enacted in 1970, sought to combat a form of pernicious cultism, or occult totalitarianism, but without listing the universal identifying characteristics of the underlying phenomenon. However, RICO is an important piece of legislation in that it officially recognized (after decades of official denial) that dissimulated, subversive/criminogenic organizations exist which have been maliciously constructed to deceive all but the most-intellectually-rigorous of investigators, and that their activities cannot be fully understood in isolation, because they form part of an overall pattern. In the end, RICO should probably be judged by the facts that that 24 'Mafia Families' are still known to survive, whilst major organized crime has become an ongoing global problem.

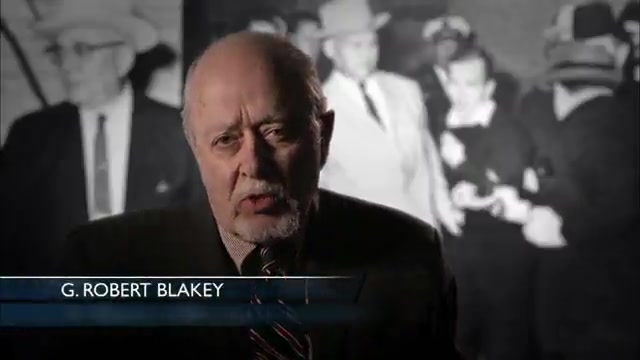

Prof. Blakey opened his report, by stating:

'It is my opinion that the Amway business is run in a manner that is parallel to that of major organized crime groups, in particular the Mafia. The structure and function of major organized crime groups, generally consisting of associated enterprises engaging in patterns of legal and illegal activity, was the prototype forming the basis for federal and state racketeering legislation that I have been involved in drafting. The same structure and function, with associated enterprises engaging in patterns of legal and illegal activity, is found in the Amway business.'

http://www.amquix.info/pdfs/Blakely_expert_report.pdf

It is my opinion that G. Robert Blakey (who apparently was only given access to a very limited amount of evidence about the 'Amway' mob), began to identify (in his particular terminology) one section of a wider criminogenic phenomenon which I have described as representing (due to its unchecked, multi-billion dollar growth and extensive infiltration of traditional culture) perhaps the greatest threat to the rule of law, of any latter-day form of pernicious cultism. Sadly, various essentially-identical 'MLM' gangs of cultic racketeers, now form a powerful global syndicate of organized crime, the existence of which is still largely-unthinkable to casual observers (including, legislators, law enforcement agents, judges and journalists).

David Brear (copyright 2023)

_______________________________________________________________________________________

The following is taken from 'Black's Law Dictionary,' page 1286 (8th ed. 2005).

In 1970, the RICO Act was passed with the purpose of attacking organized criminal activity and preserving marketplace integrity by investigating, controlling, and prosecuting persons who participate or conspire to participate in racketeering.

Racketeering has two pertinent definitions. First, racketeering may be “a system of organized crime traditionally involving the extortion of money from businesses by intimidation, violence, or other illegal methods." Id. Additionally, 18 U.S.C. §§ 1961 et seq., defines racketeering as a "pattern of illegal activity (such as bribery, extortion, fraud, and murder) carried out as part of an enterprise (such as a crime syndicate) that is owned or controlled by those engaged in the illegal activity." Id. at 1287; see also 18 U.S.C. § 1961(1) (2005). This second definition has expanded the legal conception of racketeering to contain additional crimes, including the collection of illicit gambling debts, securities fraud, and mail fraud. Id. The RICO Act is open to broad interpretation, so it may be employed in a manner unintended by Congress. In one case, the U.S. Attorney stated that a perpetrator who attacked an abortion clinic could be charged under the RICO statutes if he acted as part of an organization. Joseph Berger, Prosecutors to Present Clinic Doctor's Slaying to Grand Jury,N.Y. TIMES (Apr. 20, 1999) at B5. Commenting on a civil lawsuit brought against an anti-abortion group, one Florida Representative said, "It was never the intention that the law be used against advocacy groups." SeeClinic bomb victim speaks against bill to curb RICO, FORT WORTH STAR-TELEGRAM Jul 18, 1998 at 7. The RICO statutes can be applied in both criminal and civil cases, for a plaintiff can file a suit against a defendant for treble damages. id. at 1286. Consequently, both prosecutors and plaintiffs have reason to claim that many actions are punishable under the RICO statutes.

The Crime

18 U.S.C. § 1962 (2005).Under this section, there are three different crimes that can be committed, plus an additional conspiracy provision.

Under section 1962(a), it is a crime for any person who has received any income derived from a pattern of racketeering activity or through collection of an unlawful debt in which such person has participated as a principal, to

- use or invest, directly or indirectly, any part of such income, or the proceeds of such income,

- in acquisition of any interest in, or the establishment or operation of, any enterprise which is engaged in, or the activities of which affect, interstate or foreign commerce. 18 U.S.C. § 1961(a).

- to acquire or maintain, directly or indirectly, any interest in or control of any enterprise which is engaged in, or the activities of which affect, interstate or foreign commerce. Id. § 1962(b)

- conduct or participate, directly or indirectly, in the conduct of such enterprise's affairs through a pattern of racketeering activity or collection of unlawful debt. Id. § 1962(c)

Exception

Section 1962(a) generally does not apply to a purchase of securities on the open market for purposes of investment, and without the intention of controlling or participating in the control of the issuer, if the securities of the issuer held do not amount in the aggregate to one percent of the outstanding securities of any one class, and do not confer, either in law or in fact, the power to elect one or more directors of the issuer.) 18 U.S.C. § 1962(a).

The Punishment

18 U.S.C. § 1963 (2005).A violation of section 1962 can be punished by

- a fine,

- imprisonment for not more than 20 years, or

- both. 18 U.S.C. § 1963(a).

- a fine,

- imprisonment for up to life, or

- both. Id.

- any interest the person has acquired or maintained in violation of section 1962. 18 U.S.C. § 1963(a)(1).

- any-

- interest in any enterprise which the person has established, operated, controlled, conducted, or participated in the conduct of, in violation of section 1962; id. § 1963(a)(2)(A);

- security of any enterprise which the person has established, operated, controlled, conducted, or participated in the conduct of, in violation of section 1962; id. § 1963(a)(2)(B);

- claim against any enterprise which the person has established, operated, controlled, conducted, or participated in the conduct of, in violation of section 1962; id. § 1963(a)(2)(C); or

- property or contractual right of any kind affording a source of influence over any enterprise which the person has established, operated, controlled, conducted, or participated in the conduct of, in violation of section 1962; id. § 1963(a)(2)(D); and

- any property constituting, or derived from, any proceeds which the person obtained, directly or indirectly, from racketeering activity or unlawful debt collection in violation of section 1962. 18 U.S.C. § 1963(a)(3)

The remaining provisions of section 1963 concern forfeiture procedures.

Definitions

18 U.S.C. § 1961 (2005).Section 1961 contains a long list of definitions of what constitutes racketeering. As used in the RICO statutes,

- "racketeering activity" means

- any act or threat involving

- murder,

- kidnapping,

- gambling,

- arson,

- robbery,

- bribery,

- extortion,

- dealing in obscene matter, or

- dealing in a controlled substance or listed chemical,

- any act which is indictable under any of the following provisions of title 18, United States Code:

- Section 201 (relating to bribery),

- section 224 (relating to sports bribery),

- sections 471, 472, and 473 (relating to counterfeiting),

- section 659 (relating to theft from interstate shipment) if the act indictable under section 659 is felonious,

- section 664 (relating to embezzlement from pension and welfare funds),

- sections 891-894 (relating to extortionate credit transactions),

- section 1028 (relating to fraud and related activity in connection with identification documents),

- section 1029 (relating to fraud and related activity in connection with access devices),

- section 1084 (relating to the transmission of gambling information),

- section 1341 (relating to mail fraud),

- section 1343 (relating to wire fraud),

- section 1344 (relating to financial institution fraud),

- section 1425 (relating to the procurement of citizenship or nationalization unlawfully),

- section 1426 (relating to the reproduction of naturalization or citizenship papers),

- section 1427 (relating to the sale of naturalization or citizenship papers),

- sections 1461-1465 (relating to obscene matter),

- section 1503 (relating to obstruction of justice),

- section 1510 (relating to obstruction of criminal investigations),

- section 1511 (relating to the obstruction of State or local law enforcement),

- section 1512 (relating to tampering with a witness, victim, or an informant),

- section 1513 (relating to retaliating against a witness, victim, or an informant),

- section 1542 (relating to false statement in application and use of passport),

- section 1543 (relating to forgery or false use of passport),

- section 1544 (relating to misuse of passport),

- section 1546 (relating to fraud and misuse of visas, permits, and other documents),

- sections 1581-1591 (relating to peonage, slavery, and trafficking in persons),

- section 1951 (relating to interference with commerce, robbery, or extortion),

- section 1952 (relating to racketeering),

- section 1953 (relating to interstate transportation of wagering paraphernalia),

- section 1954 (relating to unlawful welfare fund payments),

- section 1955 (relating to the prohibition of illegal gambling businesses),

- section 1956 (relating to the laundering of monetary instruments),

- section 1957 (relating to engaging in monetary transactions in property derived from specified unlawful activity),

- section 1958 (relating to use of interstate commerce facilities in the commission of murder-for-hire),

- sections 2251, 2251A, 2252, and 2260 (relating to sexual exploitation of children),

- sections 2312 and 2313 (relating to interstate transportation of stolen motor vehicles),

- sections 2314 and 2315 (relating to interstate transportation of stolen property),

- section 2318 (relating to trafficking in counterfeit labels for phonorecords, computer programs or computer program documentation or packaging and copies of motion pictures or other audiovisual works),

- section 2319 (relating to criminal infringement of a copyright),

- section 2319A (relating to unauthorized fixation of and trafficking in sound recordings and music videos of live musical performances),

- section 2320 (relating to trafficking in goods or services bearing counterfeit marks),

- section 2321 (relating to trafficking in certain motor vehicles or motor vehicle parts),

- sections 2341-2346 (relating to trafficking in contraband cigarettes),

- sections 2421-2424 (relating to white slave traffic),

- sections 175-178 (relating to biological weapons),

- sections 229-229F (relating to chemical weapons),

- section 831 (relating to nuclear materials). Id. § 1961(1)(B).

- an act which is indictable under title 29 U.S.C. § 186 (dealing with restrictions on payments and loans to labor organizations) or 18 U.S.C. § 501(c) (relating to embezzlement from union funds). Id. § 1961(1)(C).

- any offense involving fraud connected with

- a case under title 11 (except a case under 18 U.S.C. § 157),

- fraud in the sale of securities, or

- the felonious manufacture, importation, receiving, concealment, buying, selling, or otherwise dealing in a controlled substance or listed chemical, punishable under any law of the United States. Id. § 1961(1)(D).

- any act which is indictable under the Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act. Id. § 1961(1)(E)

- any act which is indictable under the Immigration and Nationality Act,

- 8 U.S.C. § 1324 (relating to bringing in and harboring certain aliens),

- 8 U.S.C. § 1327 (relating to aiding or assisting certain aliens to enter the United States),

- 8 U.S.C. § 1328 (relating to importation of alien for immoral purpose)

- any act that is indictable under any provision listed in 18 U.S.C. § 2332b(g)(5)(B). Id. § 1961(1)(G)

- any act or threat involving

- "enterprise" includes any individual, partnership, corporation, association, or other legal entity, and any union or group of individuals associated in fact although not a legal entity. 18 U.S.C. § 1961(4).

- "pattern of racketeering activity" requires at least two acts of racketeering activity, one of which occurred after the effective date of this chapter and the last of which occurred within ten years (excluding any period of imprisonment) after the commission of a prior act of racketeering activity. 18 U.S.C. § 1961(5).

- "unlawful debt" means a debt

- incurred or contracted in gambling activity which was in violation of the law of the United States, a State or political subdivision thereof, or which is unenforceable under State or Federal law in whole or in part as to principal or interest because of the laws relating to usury, 18 U.S.C. § 1961(6)(A) and

- which was incurred in connection with the business of gambling in violation of the law of the United States, a State or political subdivision thereof, or the business of lending money or a thing of value at a rate usurious under State or Federal law, where the usurious rate is at least twice the enforceable rate. Id. § 1961(6)(B).

- "racketeering investigator" means any attorney or investigator so designated by the Attorney General and charged with the duty of enforcing or carrying into effect this chapter. 18 U.S.C. § 1961(7).

- "racketeering investigation" means any inquiry conducted by any racketeering investigator for the purpose of ascertaining whether any person has been involved in any violation of this chapter or of any final order, judgment, or decree of any court of the United States, duly entered in any case or proceeding arising under this chapter [18 USCS §§ 1961 et seq.]. 18 U.S.C. § 1961(8).

Case Law Interpreting the RICO Act

As can be clearly seen from section 1961, the list of affiliated activities is quite large and many organizations and individuals can easily find themselves subject to the stiff penalties and sanctions afforded under RICO. As a preliminary matter, it should be noted that, while the Act refers to "Criminal Organizations," membership in organized crime is not a necessary element of a RICO conviction. United States v. Uni Oil, Inc. 646 F.2d 946, 953 (5th Cir. 1981).In order to secure a conviction under the RICO Act, the government must prove both the existence of an "enterprise," and a connected "pattern of racketeering activity." United States v. Turkette, 452 U.S. 576, 583 (1981). An enterprise is an entity, and it can be proved by evidence of an ongoing organization, and by evidence that the carious associates function as a continuing unit. Id. The pattern of racketeering activity is a series of criminal acts, which can be proved by evidence of the requisite number of acts of racketeering committed by the participants in the enterprise. Id. Proof of one, however, does not necessarily prove the other. Id. Furthermore. Racketeering enterprises or racketeering predicate acts do not need to be accompanied by an underlying economic motive. NOW v. Scheidler, 510 U.S. 249, 259, 261 (1994).

To clarify how each of the three subsections of section 1962 operate, the case Kehr Packages v. Fidelcor, Inc., 926 F.2d 1406 (3rd Cir. 1991) is informative. Under section 1962(a), the plaintiff (or government) must allege an injury specifically from the use or investment of income in the named enterprise; under section 1962(b) the plaintiff (or government) must allege a specific nexus between control of a named enterprise and the alleged racketeering activity; and while section 1962(c) is not subject to these nexus limitations, cases brought under section 1962(c) cannot allege that an entity is both an enterprise and a defendant. Kehr at 1411.

In establishing a pattern of racketeering activity, the prosecutor must show that racketeering predicates are related and that they amount to or pose a threat of continued criminal activity. H.J., Inc. v. Northwestern Bell Tel, Co. 492 U.S. 229, 240 (1989). This may be done in a variety of ways. Id. at 241. "A party alleging a RICO violation may demonstrate continuity over a closed period by proving a series of related predicates extending over a substantial period of time. Predicate acts extending over a few week or months and threatening no future criminal conduct do not satisfy this requirement." Id. at 242. Congress, apparently, "was concerned in RICO with longterm criminal conduct." Id. If continuity cannot be established by showing longterm activity, "liability depends on whether the threat of continuity is demonstrated." Id. (emph. in original). Because "threat of continuity" depends on the specific facts of each case, it can be sufficiently established "where the predicates can be attributed to a defendant operating as part of a long-term association that exists for criminal purposes." Id. at 242-43. The continuity requirement can also be satisfied by showing "that the predicates are a regular way of conducting defendant's ongoing legitimate business (in the sense that it is not a business that exists for criminal purposes), or of conducting or participating in an ongoing and legitimate RICO 'enterprise.'" Id. at 243.

Defining an "enterprise" is therefore important. An enterprise can technically exist with only one actor to conduct it, even though it will, in most situations, be conducted by more than one person or entity. Salinas v. United States, 522 U.S. 52, 65 (1997) (dicta). The existence of a RICO enterprise is shown where

- there is an ongoing organization with a decision-making framework for controlling a group that remains unchanged over time

- various associates function as continuing unit, and

- enterprise is separate and apart from the pattern of racketeering activity. United States v. Sanders, 928 F.2d 940, 943 (10th Cir. 1991).