Statutory Warning

More than half a century of quantifiable evidence, proves beyond all reasonable doubt that:

- what has become popularly-known as 'Multi-Level Marketing' (aka 'Network Marketing') is nothing more than an absurd, cultic, economic pseudo-science.

- the impressive-sounding made-up term 'MLM,' is, therefore, part of an extensive, thought-stopping, non-traditional jargon which has been developed, and constantly-repeated, by the instigators, and associates, of various, copy-cat, major, and minor, ongoing organised crime groups (hiding behind labyrinths of legally-registered corporate structures) to shut-down the critical, and evaluative, faculties of victims, and of casual observers, in order to perpetrate, and dissimulate, a series of blame-the-victim rigged-market swindles or pyramid scams (dressed up as 'legitimate direct selling income opportunites'), and related advance-fee frauds (dressed up as 'legitimate training and motivation, self-betterment, programs, recruitment leads, lead generation systems,' etc.).

- Apart from an insignificant minority of exemplary shills who pretend that anyone can achieve success, the hidden overall loss/churn rate for participation in so-called 'MLM income opportunities,' has always been effectively 100%

David Brear (copyright 2018)

_________________________________________________________________________

http://mlmtheamericandreammadenightmare.blogspot.fr/2018/01/new-york-times-begins-to-investigate_11.html

Last week, I posted a jaw-dropping 'New York Times' article which contained interviews with chronic Chinese victims of the pernicious 'MLM' fairy story - one of whom had lost over US$500 000 and who now describes himself as having been 'brainwashed.' The article also explained how various US-based 'MLM' companies face investigation, or have already been caught and heavily-fined, for paying bribes in China.

Even though 'MLM' groups were once officially identified as 'evil cults and secret societies spreading superstition and lawless activities' and 'MLM' remains supposedly banned in China, the 'NY Times' article began to set out some of the subversive tactics which have been widely-employed by the bosses of various US-based 'MLM' cultic rackets in order to keep operating China.

www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-09-24/amway-embraces-china-using-harvard-guanxi

This information came as a complete surprise to one of my correspondents who wants to know how it is possible that such a controversial organisation as 'Amway' could simply buy association with Harvard University in order to gain influence over Chinese officials?

http://www.slate.com/articles/business/moneybox/2017/02/the_trump_era_will_be_a_boon_for_multilevel_marketing_companies.html

Yet these serious matters were touched on in a 'Slate Magazine' article (by Michelle Celarier) in February 2017, whilst in September 2013, a much more detailed description of 'Amway/Nutrilite's' campaign of subversion in China appeared in an issue of 'Bloomberg Markets' and was partly republished in October 2013 in the 'Washington Post.'

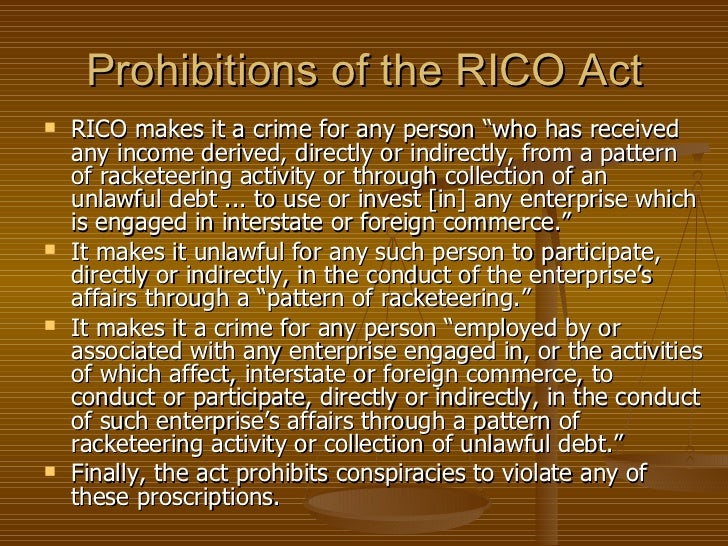

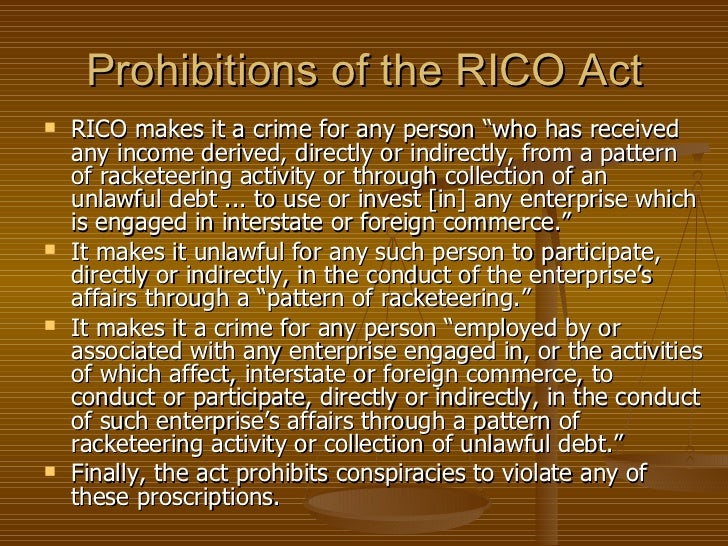

Unfortunately, the mainstream media has, to date, treated the criminogenic 'MLM' phenomenon as a business story, when nothing could be further from truth. Indeed, every move in China described by 'Bloomberg' and the 'Washington Post' in 2013 and lately confirmed by the 'NY Times,' fits into an overall pattern of ongoing major racketeering activity (as defined by the US federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organisations Act, 1970).

_________________________________________________________________________

Amway thrives in China, with Harvard’s help

|

Anthony Saich enlisted Amway to sponsor a program for Chinese officials at Harvard University's Kennedy School. (Adam Amegual/Bloomberg Markets)

|

By Bloomberg News October 4, 2013

On a sweltering July in the inland Chinese city of Hefei, 1,000 people whistle and clap as Cao Yuchao tells them about Amway, the household-products giant named after the “American Way.”

Against a rainbow backdrop and the Chinese characters for glory and dreams, Cao, Amway’s local chief, paints a glowing portrait: China has been its top market for nine years, with booming sales of Artistry cosmetics and Nutrilite dietary supplements. Amway sponsored China’s team at the 2012 Olympics.

“I can’t say for sure that these champions were successful because of Nutrilite products, but I can say for certain that every medalist has taken a Nutrilite product before walking up to the winner’s podium,” Cao says.

Amway offers great rewards, Cao tells the salespeople and recruits gathered before him: The company has paid $9.3 billion in commissions and royalties to Chinese distributors. It’s taken the best salespeople on free trips to Paris and Rome. And it gives all of its 300,000 Chinese representatives the chance to be their own boss.

Cao introduces successful representatives, who tell the audience, “Believe in yourself and nothing is impossible.” Gao Hanping, who left a job with the railway ministry for Amway, shows a video of his luxury car, a home with a garden and photos of his Las Vegas vacation.

“People say working for Amway is tough; they don’t want to do it,” Gao says. “Hard work is the key to success.”

Since its founding in small-town Michigan in 1959, Amway has pitched its direct-sales system — a corporatized version of peddlers going door to door — as a path to wealth and happiness. Now, its “American Way” depends increasingly on China, which accounted for almost 40 percent of parent company Alticor’s $11.3 billion in global revenue last year. That’s remarkable, considering that China banned direct selling 15 years ago, endangering Amway’s growth.

Amway won back its place in China by changing its business model and opening stores. It also improved its reputation by teaming up with the United States’ most prestigious school: Harvard University.

In a program bankrolled by Amway at a cost of about $1 million a year, Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government has been training Communist apparatchiks known as Amway fellows. Since it started in 2002, the program has brought more than 500 Chinese officials to Cambridge, Mass., to study public management for a few weeks. They also visit Amway’s headquarters in Ada, Mich.

In a country where nothing is more valuable than guanxi, the term for the connections considered crucial to doing business, Amway has supersized its network thanks to Harvard. Though there are no public lists of participants, Bloomberg Markets identified 50 alumni through references in résumés in official publications and on Web sites.

The Amway fellows include leaders of Henan, Ningxia and Shaanxi provinces, with a combined population of about 138 million; the party secretaries of the cities Nanjing and Wuxi; and the national vice ministers of civil affairs and industry and information technology.

Also on the list are two officials who became heads of provincial branches of China’s Food and Drug Administration, which approves the sale of nutritional products and cosmetics, Amway staples. Another alumnus is a former official in the agency that polices direct selling.

Since the program began, Amway’s sales in China have surged more than fourfold. The turnaround is all the more striking because Amway — a company dogged around the world by accusations that it’s a pyramid scheme — won over Chinese officials in part by painting itself as a crusader against such abuses. Pyramid schemes lure people to join a business that grows mainly by recruiting people rather than by selling products.

Harvard has benefited from its association with Amway. The program has raised the profile in Asia of the Kennedy School, whose mission is to train enlightened public leaders and which was less well known there than the university’s vaunted business school.

The Amway fellows get to put the prestigious imprimaturs of Harvard and its partners in China — a policy research arm of China’s State Council and Tsinghua University — on their résumés. (Of 20 fellows Bloomberg contacted, three declined comment and the rest didn’t respond to interview requests.)

Scott Balfour, vice president and lead regional counsel for Amway in Asia, says the Harvard program is just one of many the company is involved in.

“We’d have the same success without this program,” he says. “I don’t think this is a linchpin of our success, but we certainly are very proud of it.”

Amway’s guanxi with officials is impressive, says Corey Lindley, who helped Provo, Utah-based

Nu Skin Enterprises establish its skin-care direct-selling business in Asia and spent four years in China for the firm. “You have to build relationships with the government, and Amway has been a master of that,” he says.

Local government ties

Anhui, the province in which Cao presided over the July rally, shows how strong Amway’s ties to local officials can be. Hefei, 250 miles west of Shanghai, in July announced the winners of its Amway Cup, which solicited cartoons and poetry illustrating illegal pyramid schemes. The contest was sponsored by the city government, including the local Administration for Industry and Commerce, which polices direct selling.

In 2011, the province staged Anhui Sword, a campaign to combat pyramid sales schemes. In four months, the province shut down 1,302 pyramid schemes involving about 7,200 people, provincial officials announced that December.

The top official at a news conference announcing the campaign was Anhui’s vice governor, Tang Chengpei, according to another news release. Tang, who has since been promoted to provincial party secretary, was a 2002 Amway fellow.

Amway, which was founded in 1959 by Richard DeVos and his friend Jay Van Andel to sell a liquid household cleaner, has become a global giant. It employs more than 21,000 people in 100 countries and territories and sells 450 products through a network of more than 3 million “independent business owners,” its term for its non-employee sales force.

DeVos, 87, had a net worth of $8.3 billion as of Sept. 15, making him the 144th-richest person in the world, according to the

Bloomberg Billionaires Index. In addition to a 50 percent interest in Alticor, he’s the principal owner of the Orlando Magic basketball franchise and funds Christian organizations and free-enterprise groups such as the Heritage Foundation, a think tank. His son Doug, 48, is president of Amway. Van Andel, who died in 2004, was also a billionaire. His son Steve, 57, is Amway’s chairman.

Traditionally, direct sellers ply their wares to consumers face to face rather than through stores, says Bill Keep, dean of the business school at the College of New Jersey. Many such companies employ something called multilevel marketing: Their salespeople earn money not only by selling products; they also get rewarded for recruiting more salespeople — qualifying for bonuses or other compensation based on purchases made by those that they enlist, Keep says.

“The burden of recruiting and training is on the salespeople, and it lowers fixed costs for the parent firm,” he says. “But that recruitment aspect of it carries the risk of pyramid-scheme behavior.”

Therein lies a gray area, Keep says. In legitimate marketing, the main purpose is to make sales to the consumer. In a pyramid scheme, salespeople are primarily rewarded for recruiting others, he says. Telling the difference between the two requires transparency about how much of salespeople’s earnings ultimately come from selling to consumers vs. to recruits, he says. Amway says it doesn’t break down sales in that way.

“The traditional plan, which operates in most of the world, can’t be deemed a pyramid, because no one earns a thing based on the act of recruitment,” says Michael Mohr, Amway’s general counsel and secretary. “Benefit is only accrued based on the sale of product. That has been misunderstood.”

In China, Zheng Yimei, 23, heard about Amway from someone at a bus stop five years ago. Since then, she’s attended meetings in Hefei. Zheng says she wanted the opportunity to work for herself after dropping out of school at 14 and toiling as a garment worker, in a bakery and at a grocery weighing produce, where she earned 700 yuan, about $115, a month. She has bigger ambitions now.

Two salespeople in China told Bloomberg Markets how Amway’s compensation system works: The more products you sell, the higher the commission you get. One of the salespeople showed a document on the Internet that detailed the system. In the fiscal year that ended on Aug. 31, 2,500 yuan (about $410) in net sales earned a commission of 9 percent, sales of 7,500 yuan ($1,225) earned 12 percent, and on up to the top rate of 27 percent on net sales of 125,000 yuan ($20,400) or more.

The salespeople said they would also earn a bonus on the sales of each person they brought into the organization. If the salesperson made 8,000 yuan (about $1,300) in net sales and enlisted four people, who each also made 8,000 yuan in sales, he would get a 3,360 yuan ($550) bonus (18 percent of the total 40,000 yuan in revenue minus the 12 percent, or 960 yuan, that would go to each of his four recruits).

It’s not correct to say a salesperson would get a bonus for sales made by recruits, Amway’s Balfour says. The online document isn’t an Amway document and isn’t accurate, he says. The company has two categories of distributors in China: representatives, who earn commissions solely on their own sales, and authorized agents, individuals who register with the government as businesses.

“Sales representatives are true direct sellers in that they’re going out and selling the product to family and friends,” Balfour says. “Authorized agents actually have a fixed location.”

The sales from agents’ shops are counted as personal volume, he says. Under Chinese law, Balfour adds, “networks and groups are not allowed,” so Amway structures its business differently than in the rest of the world.

China’s regulations stipulate that “the remuneration paid by the direct-selling enterprise to its direct salesman shall be calculated only based on the income of the products sold to the consumers.”

In Beijing, framed photos of Amway executives with Chinese leaders going back to Jiang Zemin plaster the wall at Amway’s office, which takes up the 11th floor of a building across the street from the Ministry of Commerce.

“We have a fabulous government relations team, and the origin of that is that we were really born out of a crisis,” says Audie Wong, president of Amway’s business in China. “We had to solve crises over and over again.” Wong, 61, joined Amway in Hong Kong in 1981.

The crisis came in 1998. Amway meetings like the one in Hefei made the Chinese authorities nervous because they feared the gatherings might be a cover for religious or other rallies, says Herbert Ho, a former Amway China executive and the author of a 2004 U.S.-China Business Council report.

Entrepreneurs with fraudulent sales schemes also brought scrutiny, Ho’s report says. In one notorious case in a town in Guangdong province, a Taiwanese company persuaded farmers to buy a foot massager for 3,900 yuan — about eight times the regular price — and pay 800 yuan to join its sales force, it says.

Participants rioted when they realized they’d been scammed. Similar incidents of social unrest triggered an official backlash, according to the report.

Ban on direct selling

China banned direct selling in April 1998. The timing was lucky, Wong says, because China had begun negotiations to enter the World Trade Organization and didn’t want to be perceived as shutting down U.S. companies.

Later that year, China agreed to let Amway and other international companies continue operating, with modifications, including opening stores. Amway also began manufacturing in China and advertising there.

“We needed to demonstrate that Amway would be a long-term honorable corporate citizen in China,” Doug DeVos, Amway’s president, wrote in an article chronicling the company’s China experiences that was published in the April issue of the Harvard Business Review. The article doesn’t mention Amway’s connection to the Kennedy School.

China isn’t the only place Amway has had crises. In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission investigated the company in the 1970s for price fixing and misrepresentation of the potential profits salespeople could make. The FTC in 1979 found that Amway was not a pyramid scheme but ordered the company to stop making misleading earnings claims and fixing prices and to disclose information on the average income for its salespeople.

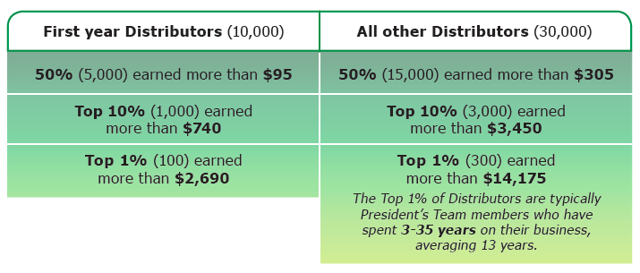

Active U.S. salespeople earn an average of $202 a month, according to company figures. Balfour says Amway doesn’t publish such information for China.

Any big company faces critics, he says. “Many of these sites or groups are operated by former distributors that were sanctioned by the company,” he says.

Mao Shoulong, a professor of public policy at Renmin University in Beijing, argues that Amway’s funding of the Harvard program is inappropriate.

“Of course this influences Amway’s position in China; they’ve got provincial governors and department heads visiting their headquarters each year,” he says. “Government officials shouldn’t be taking money from a company to travel to the U.S. or visit sites around the country.”

Says Balfour: “I don’t think our success is dependent on this program. Any educational program just helps the business environment generally.”

Corporate backing isn’t unheard of at the Kennedy School. Out of 1,049 sponsored awards from July 2000 through June, 39 were from for-profit companies such as Amway, according to school records.

The school began a push to focus more on Asia in the late 1990s and hired Anthony Saich, who had run the Ford Foundation in Beijing, to make it happen. In 1998, the school began training about 20 Chinese officials a year through a fellowship funded by New World Development, a Hong Kong-based real estate company. Lu Mai, a policy researcher for China’s State Council who had attended the Kennedy School in the 1990s, sought Saich out to propose a more ambitious initiative to train local officials.

Saich liked the idea. He drew in Tsinghua as a Chinese partner, alongside the State Council’s Development Research Center. Tsinghua had created a school of public policy in 2000, and Saich says he was eager to promote ties with it, as well as to have a partner on curriculum and training development. Money quickly became a sticking point.

“Sending 50 senior officials to America was not approved of by some people in China,” says Saich, 60, a Brit who has written or edited more than 20 books on China. “There were a lot of fears about what the program would teach.”

So Saich began looking for a company that would be willing to pay for the program in exchange for a chance to improve its relations with the Chinese government. Edward Cunningham, then a 24-year-old program officer who worked with Saich, suggested Amway. Cunningham was well versed in Amway’s travails in China; he’d written a paper about its corporate strategy there for a class at MIT, where he earned a PhD in political science. “I at least had an idea of what Amway had gone through,” says Cunningham, now an assistant professor at Boston University and director of the Asia Energy and Sustainability Initiative at the Kennedy School.

Cunningham sent a letter to Doug DeVos that ended up on Wong’s desk in Beijing. Wong saw opportunity. “It has this combination of the best brands,” Wong says, laughing. “You have Harvard, you have Tsinghua, and you have the State Council.” Amway signed up.

Amway fellows, who are selected by the Communist Party, prepare for two weeks at Tsinghua before studying government functions, such as budgeting and crisis management, at Harvard. Lectures taught by well-known Harvard faculty members — Joseph Nye, famous for his study of political power and influence, for instance — are translated into Chinese.

Saich says the sponsorship lets Amway show it’s interested in more than profits in China. “It gives them something to talk about with senior government officials,” he says. “Secondly, it probably gives them a local network base that they can interact with. They have people from the program in every single province.”

Amway has accomplished things other foreign enterprises haven’t. It was the first and only foreign company allowed to register a charitable foundation with the Ministry of Civil Affairs, Wong says.

The Kennedy School’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, which Saich heads, trains city staff from Shanghai and Indonesian and Vietnamese officials. State-owned China Southern Power Grid Co. and Thai investment firm Charoen Pokphand Group Co. have sponsored training programs at the Kennedy School, whose graduates include Bo Guagua, son of

Bo Xilai, the disgraced member of China’s ruling Politburo.

Meanwhile, in China, Amway’s network continues to grow. Zheng, the saleswoman in Hefei, is devoting herself full time to selling Amway products, though she has yet to make any money.

“Amway is my China dream,” she says. “If you speak about education, I don’t have much. If you focus on relevant work experience, I haven’t got much either. It’s my ticket to a better life.”

Bloomberg Markets/Washington Post (copyright 2013)