Statutory Warning

More than half a century of quantifiable evidence, proves beyond all reasonable doubt that:

- what has become popularly-known as 'Multi-Level Marketing' (aka 'Network Marketing') is nothing more than an absurd, cultic, economic pseudo-science.

- the impressive-sounding made-up term 'MLM,' is, therefore, part of an extensive, thought-stopping, non-traditional jargon which has been developed, and constantly-repeated, by the instigators, and associates, of various, copy-cat, major, and minor, ongoing organised crime groups (hiding behind labyrinths of legally-registered corporate structures) to shut-down the critical, and evaluative, faculties of victims, and of casual observers, in order to perpetrate, and dissimulate, a series of blame-the-victim rigged-market swindles or pyramid scams (dressed up as 'legitimate direct selling income opportunites'), and related advance-fee frauds (dressed up as 'legitimate training and motivation, self-betterment, programs, recruitment leads, lead generation systems,' etc.).

- Apart from an insignificant minority of exemplary shills who pretend that anyone can achieve success, the hidden overall net-loss/churn rate for participation in so-called 'MLM income opportunities,' has always been effectively 100%.

David Brear (copyright 2018)

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Pyramid schemes cause huge social harm in China

Ponzi schemes cause huge social harm in China. Crackdowns may not be working

THE authorities call them “business cults”. Tens of millions of people are ensnared in these pyramid schemes that use cult-like techniques to brainwash their targets and bilk them out of their money. In July 2017 victims of one such fraud held a rally in central Beijing (pictured), an extremely unusual occurrence. The police quickly dispersed it and the government, in panic, declared a three-month campaign against the scams. Hundreds of them were closed down and thousands of people arrested. But the cults are adopting new guises. The problem may still be growing.

Li Xu shows how they work and why they are so hard to fight. Mr Li was 34 when his family got him a job at Tianshi, which claimed to be a company selling cosmetics and health products in the coastal province of Jiangsu. He paid 2,800 yuan ($340) as a “joining fee” and rose quickly through the ranks. He recruited others, including his younger sister. “They gave you a vision of wealth and success,” he says. “It does wonders for your confidence.”

As he became more senior, however, Mr Li started to worry about the business. Its head office was miles from anywhere. Surrounded by colleagues day and night, he rarely saw outsiders, or customers—let alone the riches he had been promised. There is a genuine cosmetics company called Tianshi, but the firm Mr Li worked for was not it, nor did it seem to make money selling cosmetics. Rather, he thought, its revenue came from the “donations” which he, his sister and other members of the swelling workforce willingly paid out in the expectation of big returns. Eventually Mr Li realised the operation was a scam. The firm’s real business, he realised, was to trick people into handing over money and then persuade them to hoodwink others to do the same.

Mr Li left the firm and convinced his sister to do so as well. But most of his colleagues believed the company, not him. They stayed with it right up until it was closed down for breaking laws on fraud. Determined that others should not suffer as he had, Mr Li told his family that he was going to become an itinerant labourer. Instead, his travels took him in search of other victims of pyramid schemes. Most of those he found believed, like his former colleagues, that the companies which had taken their savings had their best interests at heart. Beginning with a couple of phones and volunteers, he founded and built up an NGO, the China Anti-Pyramid Promotional Association, into the main private institution taking on this warped product of China’s growth.

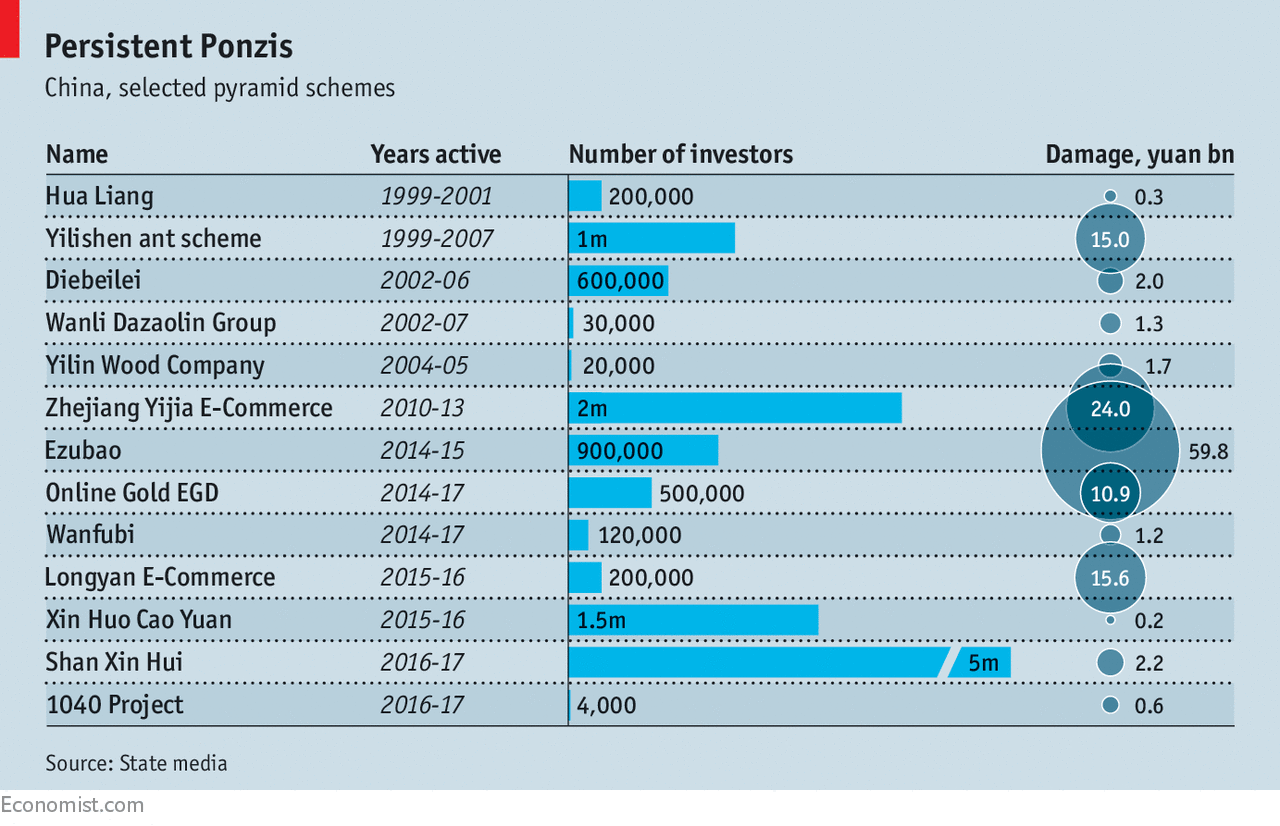

Many countries suffer from Ponzi schemes, which typically sell financial products offering extravagant rewards. They pay old investors out of new deposits, which means their liabilities exceed their assets; when recruitment falters, the schemes collapse. China is no exception. In 2016 it closed down Ezubao, a multi-billion-dollar scam that had drawn in more than 900,000 investors. By number of victims, it was the world’s largest such fraud.

Chinese pyramid schemes commonly practice “multi-level marketing” (MLM), a system whereby a salesperson earns money not just by selling a company’s goods but also from commissions on sales made by others, whom the first salesperson has recruited. People often earn more by recruiting others than from their own sales. Since 1998 China has banned the use of such methods, although it does allow some, mostly foreign, MLM companies to do business in China as “direct sellers”. This involves recruiting people to sell products at work or at home.

Family connections

The distinguishing feature of the Chinese scams is the way they combine pyramid-type operations with cult-like brainwashing. Typically, says Mr Li, a friend or family member will persuade a new recruit to go to an unfamiliar, often isolated place for a week of “introductions and training”. Cao Yuejie, for example, was enticed into joining such a scheme by her husband while on honeymoon. In many cases the recruiter (who is often duped) will spend the first three days trying to persuade the victim that the firm is a benevolent institution (not like those awful Ponzis!) and that working for it would be for the good of the family. For the next four days, the company’s representatives will appeal to the recruit’s ambition and greed, as well as his loyalty to his family.

In southern China these interactions usually take place in small groups, or one to one. In the north the persuasion is often done in groups of 30, crammed into a small room. In both systems victims sometimes have their mobile phones taken from them. They say they never have a moment to themselves. By the end, eight out of ten will leave but the last two will become converts. Once in the firm, everyone lives and eats together and sings communal songs. Some sample lyrics: “The poor shall escape their fate and the rich will gain more than they dream of.” “Invest once and your family will be rich for three generations.”

Many perfectly legal companies try to boost morale by getting staff to sing company songs or organising awaydays. China’s business cults, however, combine such techniques with violence. Zhang Chao was a 25-year-old who was trying to break away from an illegal MLM company outside the northern port city of Tianjin. He was found dead from heatstroke, dumped at the side of a road by colleagues. In another case, Cheng Cuiying and his wife walked for two days to Tianjin to rescue their son from an MLM business. They found him drowned in a lake. People were arrested in connection with both deaths. But the firms, and the money, disappeared.

Business cults seem to be growing. In the first nine months of 2017 the police brought cases against almost 6,000 of them, twice as many as in the whole of 2016 and three times the average annual number in 2005-15. This was just scratching the surface. In July 2017 the police arrested 230 leaders of Shan Xin Hui, a scheme that was launched in May 2016 and had an estimated 5m investors just 15 months later (see chart). In August 2017, after the government launched its campaign against “diehard scams”, police in the southern port of Beihai, Guangxi province, arrested 1,200 people for defrauding victims of 1.5bn yuan ($223m). One scheme in Guangxi, known as 1040 Project, was reckoned to have fleeced its targets of 600m yuan. If Mr Li’s estimate of tens of millions of victims is accurate, they must have handed over tens of billions of yuan in total.

The scale of the scams worries the government. Their cultish features make it even more anxious. The Communist Party worries about any social organisation that it does not control. Cults are especially worrisome because religious and quasi-religious activities give their followers a focus of loyalty that competes with the party. Hence the relentless repression since 1999 of Falun Gong, a spiritual movement which the government describes as a cult. Hence, too, new rules on religious activity that took effect on February 1st. They are aimed at reinforcing state control over worship, decreeing that no religion may imperil the stability of the state. The party decides what constitutes a threat. Its threshold is very low.

The case of Shan Xin Hui suggests that, although business cults are a problem, people do not blame the authorities for causing it. If anything they want the government to help the schemes. The protest in Beijing last July was held by thousands of Shan Xin Hui’s depositors. The authorities closed off roads in the city centre and sent the police to break up the demonstration. Yet the unrest was triggered not by the scam but by the arrest of the company’s bosses. “They have accused the company of pyramid selling, but they did nothing wrong. They only wanted to help poor people,” one demonstrator-investor told the Reuters news agency. “Shan Xin Hui supports the party’s leadership”, says the banner pictured on the previous page.

The authorities will find it hard to curb the scams for three main reasons. First, in order to encourage cheap loans for industry, the central bank keeps interest rates low. For years they were negative, ie, below inflation. That built up demand among China’s savers for better returns. With gross savings equal to just under half of GDP, it is not surprising that some of that pool of money should be attracted to schemes promising remarkable dividends.

Second, it is often hard for consumers to spot frauds. In 2005 China legalised direct selling, arguing that there was a distinction between that practice and the way that Ponzi schemes operate. But Qiao Xinsheng of Zhongnan University of Economics and Law argues that the difference is often “blurred” in the eyes of the public. Scammers can easily pass them themselves off as legitimate. Dodgy companies exploit government propaganda in order to pretend they have official status. For example, they may claim to be “new era” companies, borrowing a catchphrase of China’s president, Xi Jinping.

Third, argues Mr Li, business cults manipulate traditional attachments to kin.

Companies in America often appeal to individual ambition, promising to show investors how to make money for themselves. Those in China offer to help the family, or a wider group. Shan Xin Hui literally means Kind Heart Exchange. It purported to be a charity, offering higher returns to poor investors than to rich ones. (In reality everyone got scammed.) Business cults rely on one family member to recruit another, and upon the obligation that relatives feel to trust each other. This helps explain why investors who have lost life savings continue to support the companies that defrauded them.

Off with their many heads

It also explains why they are hydra-like. As the authorities shut down large business-cults, smaller ones find new ways to survive. Experts say that, increasingly, pyramid schemes are moving onto the internet. They are often relatively small, usually with hundreds or thousands of followers, not millions. They cannot rely on brainwashing in an isolated location, as face-to-face schemes do. But they are skilled at using the closed environment of social-media chat groups to replicate that kind of real-world experience. And they appear to be flourishing.

These new forms could be even more pernicious than the old because they are extending their social reach. Previously, schemes concentrated on pensioners and migrant workers, the two groups that save the most in China. The new scammers target all sorts: from the ultra-rich with money to burn; to poor students who face a tightening job market; to the children of migrant workers, struggling with poor education and falling demand for cheap labour. It was bad enough when the scammers operated mainly on the margins of society, targeting its most isolated members. Now, says Mr Li ominously, “there is a business cult for everyone.”

The Economist (copyright 2018)

No comments:

Post a Comment