In the light of recent revelations concerning the Libor rate-fixing scandal, I have been asked to re-publish my article on banksters, from 2008. This is because the underlying explanation of Libor-fixing can be found in strangely-familiar events that unfolded in the USA and Britain, many years ago. Apart from the exact wording of the script and the increasing number of zeros involved, the only things that really change in this ongoing tragicomedy, are the styles of respectable-looking costumes which the principal actors always sport.

__________________________________________________

|

| Nelson Aldrich (1841-1915) |

Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich was an American politician and businessman whom most people have now never heard of. However, what this forgettable-fellow did in the closing years of his life (and which still affects almost the entire world today) must have had the founding-fathers of the American Republic spinning in their graves; for until Aldrich came along, the non-indigenous people of the USA had managed to chart their own course towards prosperity without the need for a central banking system.

A mere 65 years before Nelson Aldrich was born, American colonists had rebelled against the increasingly corrupt ways of Europe (where central banks, national debts and paper money had appeared at the end of the 17th century).

The free-thinking men who drew up the US Constitution, were not economists, but they were blessed with a large amount of common sense. They realized that, when facing a financial storm, if unelected bankers and financiers are allowed to take the helm of a sovereign nation’s monetary policy, then the instinctual desire of a democratically- unaccountable minority to remove as much as possible from the majority, will result in the ship of state being steered towards even greater dangers.

Nelson Aldrich was once an unremarkable, but ambitious, wholesale grocer from Rhode Island. After marrying into a wealthy family in 1866, and then entering politics and ‘Freemasonry,’ he eventually became leader of the Republican party in the US Senate and Chairman of the influential Senate Finance Committee. By the time of his death, the American press referred to Senator Aldrich as the ‘General Manager of the Nation.’ Indeed, he has been widely-recognised as the helmsman of a series of radical financial changes of course which led to the creation of the US Federal Reserve System and the 16th Amendment to the US Constitution that apparently authorised the imposition of an unapportioned, federal income tax on the sale of American citizens’ own labour. However, a growing number of insightful commentators now openly-accuse Nelson Aldrich of being the corrupt dupe of banksters who, after luring him into a position of personal and financial obligation, manipulated him into introducing a devious scheme to exploit the American people via a fundamentally-unconstitutional system of perpetually-expanding debt resembling a protection racket; for since the 16th Amendment to the US Constitution was never ratified, federal income tax on labour has been unlawfully imposed on the American people (and kept in place for almost a century, contrary to various rulings of the US Supreme Court), in order that successive federal governments can continue to pay the interest on money which, since 1913, they have been obliged to keep borrowing from banksters, and which the federal government previously could print independently. Whilst a majority of Americans don’t care, or continue to believe the ‘Federal Reserve’ and ‘Internal Revenue Service’ to be essential structures conceived by their elected leaders to act in the interests of the nation, in 1913, the Federal Reserve Act transferred the United States monetary policy, including the monopoly to issue paper money, into the hands of a private bank with a misleading name. In other words, the Federal Reserve Act was quite literally a license to print money. That said, since US dollars no longer guarantee bearers payment on demand in gold, the Federal Reserve Act has, therefore, surreptitiously become a license to pass-off essentially-valueless pieces of paper as a means of exchange.

|

| J.P. Morgan |

Ironically, at the end of the 19th century, Senator Aldrich had considered the above financial reforms (which he began to implement in 1909), to be the central planks of communism (i.e. extreme, or revolutionary, socialism). However (in the intervening years), Aldrich had acquired millions of (green) reasons to change his mind. In 1906 (aged 65), he was suddenly persuaded to sell his interests in the Rhode Island Street Railway System to a New York company, the boss of which was the agent of the financier, J.P. Morgan.

|

Leopold II |

Aldrich then followed the amoral advice of a number of his financier-friends, and rapidly multiplied his already-substantial cash-windfall by investing heavily in controversial mining and rubber companies operating in the Belgian Congo. These companies began to generate indecently huge profits, and pay similar dividends, because they’d been sold the right to use slave labour by King Leopold II of Belgium (a megalomaniac who held the frighteningly familiar beliefs that he had been anointed by God and that negroes were sub-human).

In 1907, a financial crisis hit the USA and 50% was wiped off the total value of shares being traded on the New York stock exchange. Across the nation, numerous banks and trusts were besieged by their depositor/investors, forcing many of them into bankruptcy. At this moment of universal panic, J.P. Morgan coolly stepped forward, and together with a group of similarly cash-rich New York associates, offered sufficient funds to save the nation’s failing-banks, but effectively taking control of them. Later that year, when the USA was facing another financial crisis, J.P. Morgan was allowed to takeover the US Steel Corporation. However, it is now known that the panic of 1907 was almost certainly engineered by J.P. Morgan and his associates, using the age-old technique of spreading rumours. In 1908, the ‘Aldrich-Vreeland Act’ was passed. This created a ‘National Monetary Commission,’ chaired by Senator Aldrich, to investigate, and report on, the previous year’s panic. After publishing 30 (less-than-intellectually-rigorous) documents, in which the Commission members failed to identify the underlying cause of the problem and, instead, concluded that the national economy had been saved from total collapse by the injection of a convenient reserve of private capital, the Commission produced the ‘Aldrich Plan’ upon which the Federal Reserve System is still largely-based. Interestingly, it was only after he had returned from a trip to study European National Banks, that Aldrich became completely-convinced that the USA also needed a central banking system, just like Britain, France and Germany.

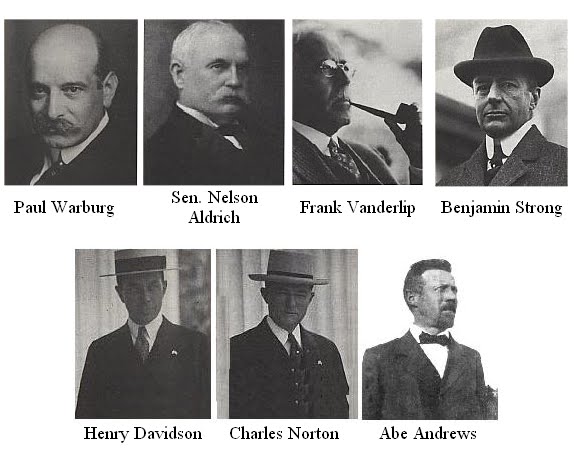

Isolated from all voices of dissent (during a mysterious meeting held on Jeykll Island off the coast of Georgia), and advised by a group of 6 co-opted economists and banksters, Paul Warburg, Frank Vanderlip, Benjamin Strong, Henry Davison, Charles Norton and Abram Andrews (representing persons already controlling 25% of the world's capital), over a period of just 10 days in 1911, Aldrich (now aged 70, and whom Paul Warburg later described as ‘bewildered’) produced his detailed plan for an American central bank.

Although it bore his name, in reality Senator Aldrich could not have been the author of this document. His judgement has been further called into question, due to the fact that his daughter, Abigail, was married to financier, John D. Rockefeller Jnr. Indeed, the Senator’s Grandson, Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller (1908-1979), would later become Republican Vice-President (alongside President Nixon’s forgettable-replacement, Gerald Ford).

So, what exactly is it that banksters will always try to do, if corrupt, and/or naïve, political leaders fail to identify them and allow them to steer a nation’s monetary policy in whatever profitable direction they want? The rather obvious answer to this important question has been known for three centuries; for, before the industrial revolution, central banking systems and many of the other so-called ‘essential structures, and instruments,’ of free-market capitalism (which have produced today’s failing global-economy) were already being installed in England without any independent regulation.

In 1694, a ‘joint-stock’ company, the ‘Bank of England,’ was created. A Royal Charter granted its Governor the monopoly to act as the English Government’s banker. Until this time, the ancient concept of money had been based on the intrinsic value of the precious metal content of a sovereign State’s coinage, but the ‘Bank of England’ was also given the monopoly to issue paper money (guaranteeing bearers payment on demand, in gold). However, thriving merchant banks, insurance and securities markets, and a stock exchange (turning over millions of pounds of business annually on promissory notes) were expanding rapidly in London at the dawn of the ‘Age of Enlightenment.’ By 1707, the United Kingdom of Great Britain had been created by the union of Scotland with England.

In 1711, the incorporation of a ‘South Sea Company’ was proposed by two London merchant/ stockbrokers, George Caswall (of Turner Caswall & Co.) and John Blunt (of the ‘Hollow Sword Blade Company’). What they initially offered, seemed to be a perfectly viable investment scheme linked to profits generated by Britain’s growing overseas trade. As such, at first glance, the ‘South Sea Company’ prospectus closely-resembled that of the ‘East India Company’ which itself was based on a variation of the theory of insurance (i.e. the off-loading of financial liability held by the few, onto the many).

In 1708, the directors of the ‘East India Company’, supported by their political allies, had, in exchange for lending the government approximately £3 millions, legally-acquired the hugely-profitable (temporary) monopoly of British trade with the ‘East Indies.’ The government's £3 millions debt to the East India Company (upon which annual interest was paid via tarifs imposed on goods imported into Britain by the East India Company), was then carved up and resold to private investors in the form of ‘East India Company’ stock (the value of which was subject to market forces). Dividends were only paid to share holders on the East India Company's actual net-trading profits. However, the instigators of the ‘South Sea scheme’ actually intended to circumvent the ‘Bank of England’s’ juicy monopolies, by deliberating creating an insolvent corporate trading-front behind which lurked another profitable, but unlawful, national bank. Unlike the 'East India Company,' this mystifying, legally-registered corporate structure would first agree to pay dividends to share holders only on net-trading profits, but then make no significant net-profits from trade; instead, the 'South Sea Company' would unlawfully pay dividends to its share holders derived from the government's annual interest payments whilst peddling more and more people an exclusive financial product derived from carving up more and more government debt. In simple terms, the so-called 'South Sea scheme' was a dissimulated closed-market swindle, or pyramid scam, without any significant source of revenue other than its own participants. As such, it was based on the crack-pot economic theory that: never-ending recruitment + never-ending payments by the recruits = never ending profits for the recruits.

|

| Robert Harley (1661-1724) |

In reality, it is now generally accepted by most historians that the 'South Sea Scheme' had been largely-devised by Edward Harley, the younger brother of Robert Harley (Britain's new Chancellor of the Exchequer), and John Blunt.

Robert Harley (a self-righteous, Nonconformist Christian and leading member of the Whig party) came to office in August 1710, at a time when government debt was spiralling out of control due to previous mis-management of the nation's finances, combined with Britain's ongoing involvement in the vastly-expensive ‘War of Spanish Succession.’ Desperate to find cash to pay the Duke of Marlborough's army fighting in Europe against Spain's allies, the French, the new Chancellor's first move was to turn away from the Bank of England. John Blunt of the 'Hollow Sword Blade Company' (a bank), along with a private banking consortium including Edward Gibbon and George Caswell, were given the right to sell £100 tickets for a national lottery. This offered all players a minimum prize of £10, but a few lucky players would get maximum prizes up to £20 000. However, the winners soon discovered that their prizes were not paid out as lump-sums. In this way, more than £1 million was raised within a few months. Blunt, Caswell and Gibbon (along with friends and relatives) pocketed huge commissions and 'expenses' for promoting the lottery and selling the tickets. Whilst all this was occurring, Robert Harley headed a parliamentary committee (including his younger brother, Edward, his brother- in-law , Paul Foley, and John Aislabie who led a group of 200 members of parliament known as the 'October Club). The committee was appointed to investigate, and calculate, the national debt. In reality, the Chancellor already knew this to be approximately £9 millions and he had also cooked up a scheme for managing it.

|

| Daniel Defoe |

In the face of political opposition, what appeared to be Blunt and Caswell's prospectus for a ‘South Sea Company,' was supported by Robert Harley, who was so enthusiastic, that he personally organised a campaign of pamphlets and editorials in newspapers. Notable poet and collector of antiquarian manuscripts himself, Robert Harley employed his literary friends as propagandists. They were some of the most talented English prose writers of the day, including Daniel Foe (a.k.a. ‘Daniel Defoe’) and Jonathan Swift. As a reward for his efforts, Robert Harley was made Earl of Oxford and promoted to the post of 'Lord High Treasurer.' Secretly, members of the British government (including Robert Harley) were already in peace talks. Consequently, rumours were rife that the 'War on Spanish Succession' was about to end and that the 'South Sea Company' was going to make its investors rich.

Behind all the pretty words and exciting images, the reality of the ‘South Sea Company’ was somewhat different. Although the instigators of the 'scheme' knew that their company was really the front for an unlawful national bank (which obviously would not make its real profits from trade), the 'scheme's' covering 'commercial' activity was intended to be the purchase of kidnapped humans in W. Africa to be transported and sold into slavery in the Americas. This horrific racket was a perfectly legal business at the time; it was falsely justified by the convenient, contemporary belief that negroes were subhumans and, therefore, no different to farm animals. After discharging their surviving human cargo, the 'South Sea Company' slave ships (which each would have a Christian Minister onboard) were to be used to transport goods to Europe.

In 1711, a joint-stock company (i.e. a corporate structure with a specified commercial purpose, initially financed by capital raised from the public sale of shares in its declared assets and projected trading profits) was legally- incorporated by Blunt and Caswall. In return for a future monopoly of British trade with South America, the ‘South Sea Company’ was permitted, by Act of Parliament, to assume liability for a portion of the British National debt. Private holders of a recent issue of government securities (with a guaranteed face-value), were obliged, by the same Act of Parliament, to exchange these for ‘South Sea Company’ stock (with a nominated value). The initial rate of exchange was determined by the government, but, thereafter, the value of the stock became subject to market forces. The company was permitted to raise extra working-capital by borrowing against the security of the future debt-repayment due from the government. The government agreed to pay the ‘South Sea Company’ 6 % annual interest (in perpetuity) on approximately £9 millions value of the national debt (fixed at the moment of exchange). However, stock-holders had no rights to a share of the approximately £568 000 annual interest and 'expenses' payments to the company. Officially, dividend payments had to depend solely on the company’s actual trading profits. Unfortunately, South American ports had been closed to British ships since the start of the war in 1703, but the government intended to fund its interest payments to the ‘South Sea Company’ from tariffs on the millions of pounds worth of goods which the company was, theoretically, going to be importing once the war was successfully concluded.

As predicted (by Robert Harley and his friends), the ‘War of Spanish Succession’ soon ended. However, as enormous international tensions remained, the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) granted Britain only limited trading rights with Spanish colonies.

Just one solitary British ship, carrying not more than 500 tons of cargo, was allowed per year. A further clause in the Treaty of Utrecht, specified a maximum annual British quota of 4800 slaves. Consequently, an immediate boom could not occur. In fact, the ‘South Sea Company’ only conducted its first, allotted slave trading during 1717, and this represented a net-loss. As they had always intended, to increase income, the company’s officers took on a further £2 millions of national debt to be converted into stock, but they now unlawfully increased the market-value of their existing stock-issue by paying dividends to share-holders using capital which they’d legally borrowed against the security of the government’s future interest payments. During 1713, the market-value of (what should have been) the technically insolvent ‘South Sea Company’ was artificially-increased by 40%. Despite the fact that, to achieve this the company officers had wilfully breached the terms of an Act of Parliament, no private investor had cause for complaint, and independent financial regulators didn’t exist. Although relations between Britain and Spain were on the slide, supporters of the ‘South Sea Company’ steadfastly denied this bleak reality, insisting that long-term prospects for future earnings were excellent.

|

| George I |

In 1718, another war with Spain broke out. South American ports were again completely closed to all British ships. Therefore, the ‘South Sea Company’s’ specified commercial purpose disappeared overnight. Since the company’s officers were only authorized to pay dividends using actual trading profits, the shareholders had become the contributing participants in an unviable system of economic exchange without a sustainable source of external revenue. Whilst the war continued, the company couldn’t conduct any trade. Self-evidently, there could be no actual profits to divide. In reality, the pieces of paper printed as ‘South Sea Company shares’ had become fake securities, because they had long-since lost their guaranteed face-value. Therefore, any unqualified ‘commercial’ vocabulary used to describe the subsequent criminal activities of the officers of the ‘South Sea Company’ should be considered a misleading use of language. Obviously, it was now impossible for everyone involved to face reality. To maintain confidence, Robert Harley and his friends had encouraged King George I to become ‘Governor of the South Sea Company.’ For a period, Britain’s Head of State was the unwitting front-man for what was soon to become one of the most convincing, and extensive, closed-market swindles in history.

| John Aislabie |

By 1719, Robert Harley had fallen from royal favour and the new ‘Chancellor of the Exchequer,’ John Aislabie, was again facing a rising national debt. This time, it was already over £50 millions. John Blunt and his ‘company cashier,’ Robert Knight, again offered salvation. In the face of competition from the ‘Bank of England,’ they proposed what they arbitrarily defined as a ‘larger joint-stock, investment scheme’ where private holders of a new issue of approximately £31 millions of government securities (with a guaranteed face-value) could voluntarily convert these into ‘new South Sea Company shares’ (with a nominated face-value). Without a full explanation of the source of their finance, Blunt and Knight offered to pay the government an immediate £7.5 millions fee for the privilege. To sweeten the deal, the pair even promised that the government would only have to pay 5% annual interest on the new debt, and that this would be lowered to 4% after 8 years. Knight then corrupted approximately 50 members of parliament and numerous friends of the King. The (freshly-Knighted) Sir George Caswall had been elected to parliament, 2 years earlier. The bribes comprised valueless pieces of paper, elaborately printed as ‘new company shares,’ but which would acquire a market-value only if the proposed ‘South Sea stock-conversion’ was voted through parliament.

|

| James Craggs the Elder |

|

| James Craggs the Younger |

|

| The Duchess of Kendal |

Recipients of the bribes included: Charles Spencer (First Lord of the Treasury), Charles Stanhope (Secretary to the Treasury), James Craggs the Elder (Postmaster General), James Craggs the Younger (Southern Secretary) and the Duchess of Kendal (the King’s favourite mistress).

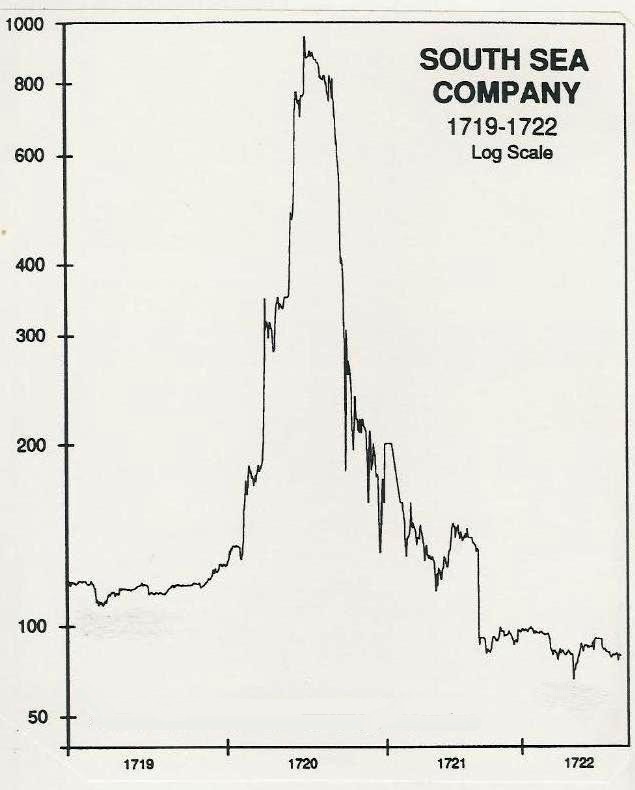

In the Spring of 1720, parliament duly passed another Act which agreed to Blunt and Knight’s so-called ‘investment scheme.’ In order to finance the new debt-acquisition, the‘company’ was given official permission to increase its number of existing ‘shares.’ However, to pay the £7.5 millions fee, the government’s own securities needed to be exchanged for ‘new South Sea Company shares’ at a nominated rate already different to the securities’ guaranteed face-value. There were some common-sense objections at the time, but, incredibly, the ‘South Sea Company directors’ were allowed to set their own rate of conversion. Obviously, the greater the nominated value of the ‘new shares’ at the moment of exchange, the greater the profits were for the ‘directors’ and for everyone whom they’d bribed. In the end, the exchange-value of the bribes alone totalled over £1.2 millions. In effect, the Parliamentary Act was a license to print, and launder, a form of counterfeit currency. Once the conversion was completed and the government was paid, the counterfeiters began to use various ruses to drive-up the market-value of their ‘new shares.’ Again, using pamphlets and newspaper editorials, exciting rumours were started about ‘secret, future trade agreements and the unlimited value of future trade with the Americas.’ When this ‘positive’ propaganda tactic worked, and share prices rose steeply, the counterfeiters then sold further issues of ‘new stock’ and started to lend cash (via their own Bank, the ‘Hollow Sword Blade Company’) against the artificially inflated market-value of their previous issues, but only to enable individuals to purchase the subsequent issues. There was a veritable mania to buy - a contagious mass-psychosis, akin to gambling fever, began to spread throughout the land. In the end, there were more than 30 000 reality-denying believers - all convinced that they couldn’t lose.

In January 1720, ‘South Sea Company shares’ were trading at approximately £130, by the end of May 1720 they were over £500. Not surprisingly, dozens of copy-cat swindles began to appear. Frustrated members of the public who felt they’d missed the boat, and who now couldn’t afford ‘South Sea Company shares,’ fell over themselves to get in on the ground floor of any ‘new prospectus’ that sounded speculative. The most infamous of these was presented as:

‘A Company for carrying on an Undertaking of Great Advantage, but nobody to know what it is.’

One morning an enterprising young man circulated a ‘prospectus’ in London’s financial quarter for a ‘joint-stock company’ that required £500 000 capital to be raised from 5000 shares to be sold at £100 each. Subscribers were to pay a £2 deposit per share which would entitle them to an annual dividend of £100 per share. The source of all the profits was to be kept an absolute secret at first. After one month, subscribers would have to pay the remaining £98 per share - only then would they be given the full explanation. An office was opened in Cornhill (opposite the Royal Exchange) at 9 o’clock the following morning. By 3 o’clock 1000 shares had been subscribed for, and the £2 deposits paid. The young man promptly closed the door of the office. He caught the first available mail-coach to Dover, and was never seen again.

The even less-sustainable ‘joint-stock’ swindles were popularly known as ‘Bubbles’. They led to a temporary weakening in public confidence in the entire London stock-market, and demands for independent regulation. In June of 1720, the ‘Royal Exchange and London Assurance Corporation Act’ (or ‘Bubble Act’) obliged all ‘joint-stock companies’ to have a Royal Charter compelling their officers only to engage in ‘authorised trading activities.’ This was not enforced for two months, but confidence returned temporarily. Predictably, the loudest supporters of the legislation had been the ‘directors’ of the ‘South Sea Company’ and their corrupt political allies. However, in order to pay-out some profits, and to maintain their own more-sustainable, but essentially identical swindle, the ‘South Sea Company directors’ needed to keep raising more capital and to keep the market-value of their ‘shares’ increasing. Since there were no external trading profits being generated, the public were merely buying infinite shares in a finite quantity of their own cash.

Apart from all the pseudo-economic mystification and ‘commercial’ shielding-terminology, the factors which fooled almost everyone, were that:

- the ‘South Sea Company’ was associated with the King and the government

- it had a Royal Charter

- its directors were now some of the most wealthy and famous Christian gentlemen in Britain

- all holders of the original share-issue had received annual dividends for 9 years

Some profits were taken when some private ‘share-holders’ re-entered reality and began to realise that it was all too good to true. When the ‘South Sea share’ price hit the psychological barrier of £1000 at the end of June 1720, public confidence finally began to crack. An increasing number of people, including the instigators themselves, then began to sell-out in a panic. The bubble started to deflate. By the second week of September,‘South Sea stock’ had lost 33% and it was still in free-fall. Fearing that the British economy might collapse, the directors of the ‘Bank of England’ (who managed about 8% of the national debt) offered their silver reserves to underwrite and stabilise ‘South Sea’ shares at £400. Many grabbed this offer, but the ‘stock’ continued to plunge. On the September 24th the ‘South Sea Company’s’ own bank stopped redeeming ‘South Sea stock.’ The directors of the ‘Bank of England’ now withdrew their previous offer, creating even more panic. Many depositors became convinced that the government’s bankers didn’t possess sufficient reserves to meet their obligations. Tens of thousands queued to withdraw their savings, and/or convert their paper money into gold. By the end of September 1720, the market-price of ‘South Sea stock’ had collapsed to approximately £135. Several thousands people (including many aristocrats) were ruined, five banks had failed. There was some rioting in London streets, whilst an unknown number of bankrupt victims committed suicide. Parliament was recalled in December and the government was forced to form a committee to investigate and report.

In the Spring of 1721, the labyrinth of lies and corruption was only partially unveiled. Many of the guilty parties remained isolated from liability. Some, including Charles Spencer and Charles Stanhope, were impeached. James Craggs (the Younger) dropped dead before he could be held to account, whilst his father (probably) committed suicide. The Craggs’ vast profits and estates were confiscated from their heirs by the Crown. John Aislabie was imprisoned. Robert Knight, had already run away to the Continent with bundles of cash. John Blunt, was arrested and put on trial. His profits and estates, along with those of his fellow ‘company officers,’ were also confiscated by the Crown. The new, First Lord of the Treasury, Robert Walpole, made sure that these seized funds were used to relieve the victims. ‘South Sea Company’ stock was divided between the ‘Bank of England’ and the ‘East India Company’ and new directors were appointed. The restructured ‘South Sea Company’ continued to trade in times of peace until the 1760s, but its principal role remained the management of government debt. It was finally wound up in the 1850s.

To give some idea of how convincing the ‘South Sea Bubble’ was at the time, the ‘Master of the Royal Mint’ and Britain’s leading mathematician, physician and astronomer, Sir Isaac Newton(1642-1727), was asked for his mathematical opinion on the rapid rise of‘South Sea Company’ stock. Newton apparently replied that he ‘could not calculate the madness of people.’ However (according to his niece), Newton lost £20 000 himself. Ironically, he also owned one of the world’s largest private collections of antiquarian books on the subject of ‘Alchemy.’

According to the ‘South Sea Company’s’ accounts, over a period of 25 years (1717-1742), 96 triangular trading voyages were undertaken and a total of 34 000 humans were purchased in W. Africa. At least 4000 (11%) did not survive the nightmare journey across the Atlantic.

David Brear (copyright 2008)

No comments:

Post a Comment