Statutory Warning

More than half a century of quantifiable evidence, proves beyond all reasonable doubt that:

- what has become popularly-known as 'Multi-Level Marketing' (aka 'Network Marketing') is nothing more than an absurd, cultic, economic pseudo-science.

- the impressive-sounding made-up term 'MLM,' is, therefore, part of an extensive, thought-stopping, non-traditional jargon which has been developed, and constantly-repeated, by the instigators, and associates, of various, copy-cat, major, and minor, ongoing organised crime groups (hiding behind labyrinths of legally-registered corporate structures) to shut-down the critical, and evaluative, faculties of victims, and of casual observers, in order to perpetrate, and dissimulate, a series of blame-the-victim rigged-market swindles or pyramid scams (dressed up as 'legitimate direct selling income opportunites'), and related advance-fee frauds (dressed up as 'legitimate training and motivation, self-betterment, programs, recruitment leads, lead generation systems,' etc.).

- Apart from an insignificant minority of exemplary shills who pretend that anyone can achieve success, the hidden overall loss/churn rate for participation in so-called 'MLM income opportunities,' has always been effectively 100%

David Brear (copyright 2018)

______________________________________________________________________________

LANZHOU, China — Feng Gang stood in front of 150 people in a conference hall in Beijing that Amway, the American marketing giant, calls its flagship “experience center.”

Introduced endearingly as Big Brother, he pitched the company’s newest product to an audience of recruits — men and women, young and old, one a street sweeper still in his orange municipal jumpsuit.

Mr. Feng said Amway’s energy drink, XS, could reduce blood-alcohol levels by as much as 70 percent. It could cure depression, he went on, or help someone who is drunk drive home. His aim: to get the crowd to go out and sell the products.

For more than a decade, scenes like this represented a financial salvation for Amway and other companies that use sales representatives to recruit others below them in what’s called multilevel marketing.

Facing declining fortunes in the United States and elsewhere, they turned to a ballooning consumer class in China hungry for new products — and susceptible to promises of the riches to be had by selling them.

Now, the future seems less promising. The giants of multilevel marketing have come under a dual assault, from regulators here and in the United States.

Two companies, Herbalife and Usana Health Sciences, disclosed last year that they faced investigations in the United States for their operations in China under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which prohibits American companies from bribing foreign officials. Another, Nu Skin, settled a similar case with the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2016, while Avon Products pleaded guilty in 2014, resulting in a $135 million fine.

Amway, which is not public, has not disclosed any inquiries by American regulators. In one Chinese province, however, the conduct of some Amway sales distributors prompted an investigation, one that the victims say was squelched by local officials, including at least one with ties to the company.

“This industry is absolute chaos for China,” said You Yunfan, a former Amway distributor who wrote a scathing memoir under the pen name Xiao Fei.

Noting that Chinese law prohibits many of the worst practices associated with multilevel marketing, he added, “The root problem is that the government is riddled with corruption and not doing its job.”

That may be changing. Four government agencies last year announced a crackdown on the marketing model, which critics denounce as a pyramid scheme.

Turbulence in the Chinese market could be devastating for Amway, which has relied on China for much of its growth over the last decade.

It is now, by far, the largest of the multilevel marketing companies here, with 1.5 million distributors, more than all the others combined, according to the Ministry of Commerce’s records. China is now Amway’s largest market, accounting for $2.6 billion in revenue, or about 30 percent of its worldwide sales, the company’s president, Doug DeVos, told Reuters last year.

In a statement, an Amway vice president, Scott Balfour, said the company welcomed the crackdown, saying it would distinguish pyramid schemes from legitimate direct selling.

Amway has not been singled out in the campaign, and it has built an impressive brand here, operating gleaming showrooms in Beijing and elsewhere and sponsoring the Chinese Olympic team. Yet it has been dogged by accusations like those it has faced elsewhere.

Former Amway distributors have organized online to warn others of the company’s model. Amway’s name in Chinese, an li, has entered the vernacular to mean to “promote heavily” or to “be brainwashed.”

Amway and others faced skepticism from the authorities nearly from the moment they entered the market in the early 1990s. Multilevel marketing was officially denounced as an “economic cult,” and in 1998 the government banned all direct selling.

Only when negotiating entry into the World Trade Organization did China agree to American demands to allow the companies in. Direct selling has been legal since 2005, though with restrictions intended to discourage the endless recruiting of new distributors, a component of Amway’s model.

Enforcement of the laws, however, remains uneven. “It’s a gray area,” said Liu Kaixiang, a professor at Peking University’s School of Law who conducts research at the university’s industry-affiliated direct-selling research center. “The majority of these direct-selling companies are right on the edge. If they were to completely follow the law, there would be no market at all.”

The vagaries of Chinese regulations and an avaricious bureaucracy have already ensnared others, like Avon, once the top direct seller here. In 2014, it admitted to providing $8 million in cash and gifts like Gucci purses to Chinese officials.

Similar troubles caught up with Nu Skin, which settled a case by the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2016 by admitting that it paid the equivalent of $154,000 to “a charity to obtain the influence of a high-ranking Chinese Communist Party official” to resolve a potential fine.

Herbalife disclosed in a stock filing that it, too, was under investigation, while Usana Health Sciences announced that it had alerted the Department of Justice about questions over “expense reimbursement policies” of its subsidiary in China.

Amway said in its statement that it had not faced questions from American regulators about its practices in China. Its business has nonetheless raised questions.

In Amway’s Beijing center, a reporter with The New York Times listened as Big Brother Feng detailed sales tactics that would violate Chinese law if used, promising that new recruits could earn more as they recruited others.

A few days later, one of the recruits was out on the streets repeating the pitch as he handed out fliers for the XS energy drink. The fliers said new distributors could ultimately earn the equivalent of $75,000 a year.

In fact, 96 percent of direct sellers make less than $750 a year, roughly the average monthly wage for private-sector workers, according to government statistics.

In some regions, Amway in particular has come under focus.

In Lanzhou, a city of nearly 3.7 million along the Yellow River and the ancient Silk Road in Gansu Province, dozens of former distributors have accused the company of abetting extortionate practices that left them in debt. They accused those above them of conning them into buying products they could not realistically sell.

One of them, Liu Gang, said he had been persuaded to give up a job as a teacher in 2009 to pursue an Amway fortune.

In training sessions, some of which he recorded and played for The Times, he was told that the way to achieve success was by working under pressure. He took out loans — first mortgaging his home, then borrowing from unofficial lenders working, he and others said, with the local Amway staff — to load up on vitamins, water filters and soaps. By 2014, he could not unload his merchandise and faced $600,000 in debt.

“I was brainwashed,” Mr. Liu said.

The provincial office of the State Administration for Industry and Commerce, which regulates businesses, took the accusations seriously. In May 2016, the office sent a letter to complainants saying that there was evidence of wrongdoing and that the region’s top two distributors, a husband-and-wife team, Tang Jinsong and Zhao Yufang, “are suspected of operating a pyramid scheme.”

“To climb to the top, you need a team of distributors under you,” said Liu Jianhong, another former distributor, who provided the letter to The Times. “It forms a pyramid. We were at the very bottom.”

Mr. Balfour, the Amway vice president, said that the Lanzhou situation had “involved a number of serious violations of our rules of conduct, as well as violations of Chinese lending laws” by sales distributors, but that the company itself had not been accused of wrongdoing.

In a second statement, Amway said that it did not endorse exaggerated claims of distributors and that company policy prohibited obtaining loans to buy products. Mr. Balfour said the company would investigate specific claims brought to its attention.

The regulatory office in Lanzhou gave enough credence to the complaints that it referred the findings to the local branch of China’s main law enforcement agency, the Public Security Bureau.

Then the investigation stalled.

Wang Xingwei, the administration official in charge of the initial investigation, said in a telephone interview that he had been transferred off the case.

The former distributors said they believed that regional officials sympathetic to Amway had quashed their complaints. They cited an instance when the state television channel in Gansu, after interviewing them, received a directive not to report on their case.

According to a journalist at the station, Gao Zenglei, the directive came from the Communist Party’s provincial propaganda department. At the time, it was headed by Liang Yanshun, who once participated in an Amway program that enrolled officials in classes at Tsinghua University and Harvard University, according to Harvard and his online biography. Mr. Liang did not respond to requests for comment.

Ms. Zhao, one of the top distributors, dismissed the accusations and said she and her husband, Mr. Tang, had done everything “entirely in accordance with the company’s system, according to the company’s operating model and under the oversight of the company.”

The aggrieved distributors, she added, were responsible for any debts they built up.

“Everyone should be responsible for their own actions,” she said. “If they don’t know this, they won’t last in this world.”

Mr. Balfour said Amway had punished individuals involved, though he did not disclose names or sanctions. Amway’s website still counts Mr. Tang and Ms. Zhao as among its top handful of sales distributors, and their photo is on display at Amway’s big Beijing conference hall.

The former distributors, by contrast, face financial ruin.

Liu Jianhong amassed $300,000 in debt. In China, that means she has been put on a government list that prohibits her from flying, taking trains or acquiring new credit cards.

“I’m going to be dealing with this the rest of my life,” she said.

Ryan McMorrow

Stevn Lee Myers

New York Times (copyright 2018)

__________________________________________________

Even though 'MLM' groups were once officially identified as 'evil cults and secret societies spreading superstition and lawless activities' and 'MLM' remains supposedly banned in China, the 'NY Times' article began to set out some of the subversive tactics which have been widely-employed by the bosses of various US-based 'MLM' cultic rackets in order to keep operating China.

www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-09-24/amway-embraces-china-using-harvard-guanxi

This information came as a complete surprise to one of my correspondents who wants to know how it is possible that such a controversial organisation as 'Amway' could simply buy association with Harvard University in order to gain influence over Chinese officials?

http://www.slate.com/articles/business/moneybox/2017/02/the_trump_era_will_be_a_boon_for_multilevel_marketing_companies.html

Yet these serious matters were touched on in a 'Slate Magazine' article (by Michelle Celarier) in February 2017, whilst in September 2013, a much more detailed description of 'Amway/Nutrilite's' campaign of subversion in China appeared in an issue of 'Bloomberg Markets' and was partly republished in October 2013 in the 'Washington Post.'

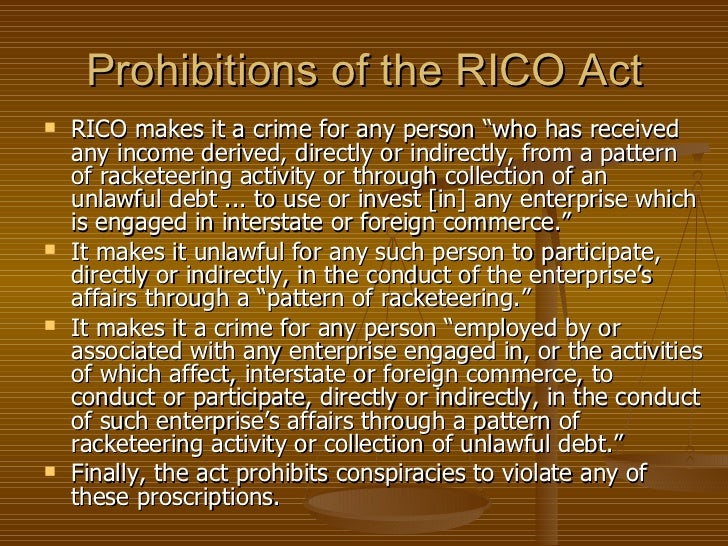

Unfortunately, the mainstream media has treated 'MLM' as a business story, when nothing could be further from truth. Indeed, every move in China described by 'Bloomberg' and the 'Washington Post' in 2013 and lately confirmed by the 'NY Times,' fits into an overall pattern of ongoing major racketeering activity (as defined by the US federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organisations Act, 1970).

_________________________________________________________________________

Amway thrives in China, with Harvard’s help

|

Anthony Saich enlisted Amway to sponsor a program for Chinese officials at Harvard University's Kennedy School. (Adam Amegual/Bloomberg Markets)

|

On a sweltering July in the inland Chinese city of Hefei, 1,000 people whistle and clap as Cao Yuchao tells them about Amway, the household-products giant named after the “American Way.”

Against a rainbow backdrop and the Chinese characters for glory and dreams, Cao, Amway’s local chief, paints a glowing portrait: China has been its top market for nine years, with booming sales of Artistry cosmetics and Nutrilite dietary supplements. Amway sponsored China’s team at the 2012 Olympics.

“I can’t say for sure that these champions were successful because of Nutrilite products, but I can say for certain that every medalist has taken a Nutrilite product before walking up to the winner’s podium,” Cao says.

Amway offers great rewards, Cao tells the salespeople and recruits gathered before him: The company has paid $9.3 billion in commissions and royalties to Chinese distributors. It’s taken the best salespeople on free trips to Paris and Rome. And it gives all of its 300,000 Chinese representatives the chance to be their own boss.

Cao introduces successful representatives, who tell the audience, “Believe in yourself and nothing is impossible.” Gao Hanping, who left a job with the railway ministry for Amway, shows a video of his luxury car, a home with a garden and photos of his Las Vegas vacation.

“People say working for Amway is tough; they don’t want to do it,” Gao says. “Hard work is the key to success.”

Since its founding in small-town Michigan in 1959, Amway has pitched its direct-sales system — a corporatized version of peddlers going door to door — as a path to wealth and happiness. Now, its “American Way” depends increasingly on China, which accounted for almost 40 percent of parent company Alticor’s $11.3 billion in global revenue last year. That’s remarkable, considering that China banned direct selling 15 years ago, endangering Amway’s growth.

Amway won back its place in China by changing its business model and opening stores. It also improved its reputation by teaming up with the United States’ most prestigious school: Harvard University.

In a program bankrolled by Amway at a cost of about $1 million a year, Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government has been training Communist apparatchiks known as Amway fellows. Since it started in 2002, the program has brought more than 500 Chinese officials to Cambridge, Mass., to study public management for a few weeks. They also visit Amway’s headquarters in Ada, Mich.

In a country where nothing is more valuable than guanxi, the term for the connections considered crucial to doing business, Amway has supersized its network thanks to Harvard. Though there are no public lists of participants, Bloomberg Markets identified 50 alumni through references in résumés in official publications and on Web sites.

The Amway fellows include leaders of Henan, Ningxia and Shaanxi provinces, with a combined population of about 138 million; the party secretaries of the cities Nanjing and Wuxi; and the national vice ministers of civil affairs and industry and information technology.

Also on the list are two officials who became heads of provincial branches of China’s Food and Drug Administration, which approves the sale of nutritional products and cosmetics, Amway staples. Another alumnus is a former official in the agency that polices direct selling.

Since the program began, Amway’s sales in China have surged more than fourfold. The turnaround is all the more striking because Amway — a company dogged around the world by accusations that it’s a pyramid scheme — won over Chinese officials in part by painting itself as a crusader against such abuses. Pyramid schemes lure people to join a business that grows mainly by recruiting people rather than by selling products.

Harvard has benefited from its association with Amway. The program has raised the profile in Asia of the Kennedy School, whose mission is to train enlightened public leaders and which was less well known there than the university’s vaunted business school.

The Amway fellows get to put the prestigious imprimaturs of Harvard and its partners in China — a policy research arm of China’s State Council and Tsinghua University — on their résumés. (Of 20 fellows Bloomberg contacted, three declined comment and the rest didn’t respond to interview requests.)

Scott Balfour, vice president and lead regional counsel for Amway in Asia, says the Harvard program is just one of many the company is involved in.

“We’d have the same success without this program,” he says. “I don’t think this is a linchpin of our success, but we certainly are very proud of it.”

Amway’s guanxi with officials is impressive, says Corey Lindley, who helped Provo, Utah-based Nu Skin Enterprises establish its skin-care direct-selling business in Asia and spent four years in China for the firm. “You have to build relationships with the government, and Amway has been a master of that,” he says.

Local government ties

Anhui, the province in which Cao presided over the July rally, shows how strong Amway’s ties to local officials can be. Hefei, 250 miles west of Shanghai, in July announced the winners of its Amway Cup, which solicited cartoons and poetry illustrating illegal pyramid schemes. The contest was sponsored by the city government, including the local Administration for Industry and Commerce, which polices direct selling.

In 2011, the province staged Anhui Sword, a campaign to combat pyramid sales schemes. In four months, the province shut down 1,302 pyramid schemes involving about 7,200 people, provincial officials announced that December.

The top official at a news conference announcing the campaign was Anhui’s vice governor, Tang Chengpei, according to another news release. Tang, who has since been promoted to provincial party secretary, was a 2002 Amway fellow.

Amway, which was founded in 1959 by Richard DeVos and his friend Jay Van Andel to sell a liquid household cleaner, has become a global giant. It employs more than 21,000 people in 100 countries and territories and sells 450 products through a network of more than 3 million “independent business owners,” its term for its non-employee sales force.

DeVos, 87, had a net worth of $8.3 billion as of Sept. 15, making him the 144th-richest person in the world, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. In addition to a 50 percent interest in Alticor, he’s the principal owner of the Orlando Magic basketball franchise and funds Christian organizations and free-enterprise groups such as the Heritage Foundation, a think tank. His son Doug, 48, is president of Amway. Van Andel, who died in 2004, was also a billionaire. His son Steve, 57, is Amway’s chairman.

Traditionally, direct sellers ply their wares to consumers face to face rather than through stores, says Bill Keep, dean of the business school at the College of New Jersey. Many such companies employ something called multilevel marketing: Their salespeople earn money not only by selling products; they also get rewarded for recruiting more salespeople — qualifying for bonuses or other compensation based on purchases made by those that they enlist, Keep says.

“The burden of recruiting and training is on the salespeople, and it lowers fixed costs for the parent firm,” he says. “But that recruitment aspect of it carries the risk of pyramid-scheme behavior.”

Therein lies a gray area, Keep says. In legitimate marketing, the main purpose is to make sales to the consumer. In a pyramid scheme, salespeople are primarily rewarded for recruiting others, he says. Telling the difference between the two requires transparency about how much of salespeople’s earnings ultimately come from selling to consumers vs. to recruits, he says. Amway says it doesn’t break down sales in that way.

“The traditional plan, which operates in most of the world, can’t be deemed a pyramid, because no one earns a thing based on the act of recruitment,” says Michael Mohr, Amway’s general counsel and secretary. “Benefit is only accrued based on the sale of product. That has been misunderstood.”

In China, Zheng Yimei, 23, heard about Amway from someone at a bus stop five years ago. Since then, she’s attended meetings in Hefei. Zheng says she wanted the opportunity to work for herself after dropping out of school at 14 and toiling as a garment worker, in a bakery and at a grocery weighing produce, where she earned 700 yuan, about $115, a month. She has bigger ambitions now.

Two salespeople in China told Bloomberg Markets how Amway’s compensation system works: The more products you sell, the higher the commission you get. One of the salespeople showed a document on the Internet that detailed the system. In the fiscal year that ended on Aug. 31, 2,500 yuan (about $410) in net sales earned a commission of 9 percent, sales of 7,500 yuan ($1,225) earned 12 percent, and on up to the top rate of 27 percent on net sales of 125,000 yuan ($20,400) or more.

The salespeople said they would also earn a bonus on the sales of each person they brought into the organization. If the salesperson made 8,000 yuan (about $1,300) in net sales and enlisted four people, who each also made 8,000 yuan in sales, he would get a 3,360 yuan ($550) bonus (18 percent of the total 40,000 yuan in revenue minus the 12 percent, or 960 yuan, that would go to each of his four recruits).

It’s not correct to say a salesperson would get a bonus for sales made by recruits, Amway’s Balfour says. The online document isn’t an Amway document and isn’t accurate, he says. The company has two categories of distributors in China: representatives, who earn commissions solely on their own sales, and authorized agents, individuals who register with the government as businesses.

“Sales representatives are true direct sellers in that they’re going out and selling the product to family and friends,” Balfour says. “Authorized agents actually have a fixed location.”

The sales from agents’ shops are counted as personal volume, he says. Under Chinese law, Balfour adds, “networks and groups are not allowed,” so Amway structures its business differently than in the rest of the world.

China’s regulations stipulate that “the remuneration paid by the direct-selling enterprise to its direct salesman shall be calculated only based on the income of the products sold to the consumers.”

In Beijing, framed photos of Amway executives with Chinese leaders going back to Jiang Zemin plaster the wall at Amway’s office, which takes up the 11th floor of a building across the street from the Ministry of Commerce.

“We have a fabulous government relations team, and the origin of that is that we were really born out of a crisis,” says Audie Wong, president of Amway’s business in China. “We had to solve crises over and over again.” Wong, 61, joined Amway in Hong Kong in 1981.

The crisis came in 1998. Amway meetings like the one in Hefei made the Chinese authorities nervous because they feared the gatherings might be a cover for religious or other rallies, says Herbert Ho, a former Amway China executive and the author of a 2004 U.S.-China Business Council report.

Entrepreneurs with fraudulent sales schemes also brought scrutiny, Ho’s report says. In one notorious case in a town in Guangdong province, a Taiwanese company persuaded farmers to buy a foot massager for 3,900 yuan — about eight times the regular price — and pay 800 yuan to join its sales force, it says.

Participants rioted when they realized they’d been scammed. Similar incidents of social unrest triggered an official backlash, according to the report.

Ban on direct selling

China banned direct selling in April 1998. The timing was lucky, Wong says, because China had begun negotiations to enter the World Trade Organization and didn’t want to be perceived as shutting down U.S. companies.

Later that year, China agreed to let Amway and other international companies continue operating, with modifications, including opening stores. Amway also began manufacturing in China and advertising there.

“We needed to demonstrate that Amway would be a long-term honorable corporate citizen in China,” Doug DeVos, Amway’s president, wrote in an article chronicling the company’s China experiences that was published in the April issue of the Harvard Business Review. The article doesn’t mention Amway’s connection to the Kennedy School.

China isn’t the only place Amway has had crises. In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission investigated the company in the 1970s for price fixing and misrepresentation of the potential profits salespeople could make. The FTC in 1979 found that Amway was not a pyramid scheme but ordered the company to stop making misleading earnings claims and fixing prices and to disclose information on the average income for its salespeople.

Active U.S. salespeople earn an average of $202 a month, according to company figures. Balfour says Amway doesn’t publish such information for China.

Any big company faces critics, he says. “Many of these sites or groups are operated by former distributors that were sanctioned by the company,” he says.

Mao Shoulong, a professor of public policy at Renmin University in Beijing, argues that Amway’s funding of the Harvard program is inappropriate.

“Of course this influences Amway’s position in China; they’ve got provincial governors and department heads visiting their headquarters each year,” he says. “Government officials shouldn’t be taking money from a company to travel to the U.S. or visit sites around the country.”

Says Balfour: “I don’t think our success is dependent on this program. Any educational program just helps the business environment generally.”

Corporate backing isn’t unheard of at the Kennedy School. Out of 1,049 sponsored awards from July 2000 through June, 39 were from for-profit companies such as Amway, according to school records.

The school began a push to focus more on Asia in the late 1990s and hired Anthony Saich, who had run the Ford Foundation in Beijing, to make it happen. In 1998, the school began training about 20 Chinese officials a year through a fellowship funded by New World Development, a Hong Kong-based real estate company. Lu Mai, a policy researcher for China’s State Council who had attended the Kennedy School in the 1990s, sought Saich out to propose a more ambitious initiative to train local officials.

Saich liked the idea. He drew in Tsinghua as a Chinese partner, alongside the State Council’s Development Research Center. Tsinghua had created a school of public policy in 2000, and Saich says he was eager to promote ties with it, as well as to have a partner on curriculum and training development. Money quickly became a sticking point.

“Sending 50 senior officials to America was not approved of by some people in China,” says Saich, 60, a Brit who has written or edited more than 20 books on China. “There were a lot of fears about what the program would teach.”

So Saich began looking for a company that would be willing to pay for the program in exchange for a chance to improve its relations with the Chinese government. Edward Cunningham, then a 24-year-old program officer who worked with Saich, suggested Amway. Cunningham was well versed in Amway’s travails in China; he’d written a paper about its corporate strategy there for a class at MIT, where he earned a PhD in political science. “I at least had an idea of what Amway had gone through,” says Cunningham, now an assistant professor at Boston University and director of the Asia Energy and Sustainability Initiative at the Kennedy School.

Cunningham sent a letter to Doug DeVos that ended up on Wong’s desk in Beijing. Wong saw opportunity. “It has this combination of the best brands,” Wong says, laughing. “You have Harvard, you have Tsinghua, and you have the State Council.” Amway signed up.

Amway fellows, who are selected by the Communist Party, prepare for two weeks at Tsinghua before studying government functions, such as budgeting and crisis management, at Harvard. Lectures taught by well-known Harvard faculty members — Joseph Nye, famous for his study of political power and influence, for instance — are translated into Chinese.

Saich says the sponsorship lets Amway show it’s interested in more than profits in China. “It gives them something to talk about with senior government officials,” he says. “Secondly, it probably gives them a local network base that they can interact with. They have people from the program in every single province.”

Amway has accomplished things other foreign enterprises haven’t. It was the first and only foreign company allowed to register a charitable foundation with the Ministry of Civil Affairs, Wong says.

The Kennedy School’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, which Saich heads, trains city staff from Shanghai and Indonesian and Vietnamese officials. State-owned China Southern Power Grid Co. and Thai investment firm Charoen Pokphand Group Co. have sponsored training programs at the Kennedy School, whose graduates include Bo Guagua, son of Bo Xilai, the disgraced member of China’s ruling Politburo.

Meanwhile, in China, Amway’s network continues to grow. Zheng, the saleswoman in Hefei, is devoting herself full time to selling Amway products, though she has yet to make any money.

“Amway is my China dream,” she says. “If you speak about education, I don’t have much. If you focus on relevant work experience, I haven’t got much either. It’s my ticket to a better life.”

Bloomberg Markets/Washington Post (copyright 2013)

Bloomberg Markets/Washington Post (copyright 2013)

David do you know if your Blog can be read in China?

ReplyDeleteAnonymous - China does not feature on my Blog's audience Stats.

Deletehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_censorship_in_China

Anonymous - Correction. I've now been informed that my Blog can be read in China. However, I don't know how many page vists my Blog has had from China, because China is has not been high on the list.

DeleteI thought all endless chain schemes offering to pay commission to participants based on their own sales/purchases and on their recruits' sales/purchases, are absolutely prohibited in China.

ReplyDeleteAnon - You thought correctly. Unfortunately, common-sense reveals that if you pass a law, but then don't enforce it, you are actually authorising what ever your law was supposedly trying to prohibit.

Deletehttp://www.ecns.cn/2017/08-15/269317.shtml

ReplyDeleteA national campaign against pyramid schemes has been launched to try to prevent the public from falling prey to the die-hard scams that have led to four deaths since the beginning of July.

A notice was issued on Monday by four ministries to crack down on gangs operating pyramid schemes, which lure job seekers under the guise of regular job recruitment.

Once the job seekers are in place, they are kept in dorms and are told, often under duress, to recruit others and to solicit money from friends and family.

The State Administration for Industry and Commerce said in the notice that it will work with the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Public Security to fight such illegal schemes, regulate companies' hiring procedures and offer job-seeking advice for school graduates.

The four ministries' campaign to eliminate pyramid scheme gangs will last from Tuesday to Nov 15. They pledged to severely punish pyramid scammers and promised to establish a long-term way to deal with such scams.

The notice was handed out after recent reports of four deaths in connection with pyramid scams.

Police in Zhongxiang, Hubei province, reported the death of a 20-year-old female student, Lin Huarong, who was said to have been lured from Hunan province to a pyramid scheme gang and was found drowned in a river on Aug 4.

Five people who are suspected of being the gang members were detained on suspicion of being involved in the student's death.

And recently, two deaths in connection with pyramid scams were reported by police in Tianjin and one similar death was reported in Shanxi province.

The three people were all in their 20s and were all offered false positions.

One of the victims, Li Wenxing, 23, a university graduate from Shandong province, believed a fraudulent employment advertisement and was lured to the gang on May 20 hoping to be offered a regular IT job. He paid an enrollment fee and was forced to stay in the organization's dormitory in Tianjin.

Li's body was found on July 14 in a pond.

http://ethanvanderbuilt.com/2017/08/16/china-is-facing-a-mlm-pyramid-scheme-epidemic/

ReplyDeleteIn 2005, the Chinese Government enacted a law called “Regulation of Direct Sales and Regulation on Prohibition of Chuanxiao” (where Chuanxiao stand for MLM). With this regulation China makes it clear that while Direct Sales is permitted in the mainland, Multi-Level Marketing is not.

Here is the reason China gives for prohibiting Multi-Level Marketing:

“Because of the multi-level payment structure, the organizers and the members at top level obtain interest illegally and, according to the Chinese Government, disturb normal economic order, and affect social stability.”

Anon - I think it would be far more accurate to say that the Chinese government only says that it has 'prohibited MLM' (rackets), whilst in reality, the pernicious fairy story, entitled 'MLM,' has been steadily gnawing its way into Chinese culture virtually unopposed.

DeleteFuck! MLM prohibited in China. Unless he knows something we don't, Carl Icahn must be mad to risk clinging to his HLF investment when the Chinese might be getting ready to burn the company!

DeleteSteven -

DeleteMore than 20 years ago, the government-controlled Chinese media recognised 'MLM' groups in general, and 'Amway' in particular, as:

"Evil cults and secret societies spreading superstition and lawless activities.'

At that time, 'Amway/MLM' was challenged, not by toothless commercial regulatory agencies, but by a ruthless Chinese internal state security agency. Some deluded Chinese Ambots who had rioted in protest were hauled off and vanished. 'MLM' was initially kicked out of China, but it subsequently sneaked back in as part of a much wider trade deal which supposedly allowed US-based companies like 'Amway', 'Herbalife', 'NuSkin', 'USANA', etc, exclusively to pursue traditional direct selling in mainland China. In reality, all these gangs of 'MLM' racketeers have followed their usual subversive tactics in mainland China and have driven a coach and horses through the technical legislation.

Thus, I'm confident that there are officials in China (but probably not in commercial regulatory agencies) who are fully-ware that, for decades, a growing number of gangs of sanctimonious racketeers behind so-called ‘MLM direct selling companies,' have successfully dissimulated vast, blame-the victim, closed-market swindles and related advance fee frauds, simply by supplying endless-chains of constantly-churning, ill-informed recruits with banal, but grossly-overpriced (and, therefore, effectively-unsaleable) products, and/or services. This cleverly constructed big-lie, has enabled the same cultic racketeers to launder billions of dollars of unlawful losing investment payments (made on the false-expectation of future reward) as ‘lawful sales (based on value and demand).’

According to the latest media reports, it seems that the Chinese officials who have known what is going on, might soon be in a position again to try to burn the entire 'MLM' fairy story.

What about the Chinese MLM "Tiens?"

Deletehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiens_Group

Wikipedia says Tiens started in 1995 and is in more than 100 countries.

Does Tiens break the law in China?

Can it be right Tiens has 16 million customers and more than 12 million sellers, when thats just over one customer per seller?

Anon - Thank-you for the 'Tiens' link you sent.

Delete'Tiens' is an 'Amway' copy-cat with more than just a touch of 'Scientology' thrown in for good measure.

Right now, I have no idea who really controls 'Tiens' or how it was allowed to become established in China. I also have no idea if the bosses of the 'Tiens' racket have been thieving from the people of China. They've certainly been thieving from the rest of the world.

The information on Wikipedia concerning 'Tiens' dates from 2009 and probably derives from 'Tiens' itself. I think it is safe to assume that there has been little difference between 'Tiens customers' and 'Tiens sellers.'

Notice how the bosses of the 'Tiens' racket do not publicly declare how many persons in total have signed contracts (no matter how they were arbitrarily defined in these take-it or leave it documents) with the organisation since it was first instigated.

Yet again, I've been contacted by a journalist wanting to know why I say that 'MLM' companies are frauds when "they offer goods for sale?"

ReplyDeleteThe following is my standard response to this FAQ.

In 'MLM' rackets, the innocent looking products/sevices' function is to hide what is really occurring - i.e The operation of an unlawful, intrinsically fraudulent, rigged-market where effectively no (transient) participant can generate an overall net-profit, because the market is in a permanent state of collapse and requires its (transient) participants to keep finding further (transient) participants.

Meanwhile a tiny (permanent) minority rake in vast profits by selling into the rigged-market and by controlling all key-information concerning the rigged-market's actual catastrophic, ever-shifting results from its never- ending chain of (transient) losing participants.

It is possible to use any product or service to dissimulate a rigged-market swindle aka pyramid scheme. There are even some 'MLM' rackets which have hidden behind well-known traditional brands (albeit offered at fixed high prices).

In 'MLM' rackets, there has been no significant or sustainable source of revenue other than never-ending chains of contractees of the 'MLM' front companies. These front-companies always pretend that their products/services are high quality and reasonably-priced and that they can be sold on for a profit based on value and demand. In reality, the underlying reason why it's mainly only been 'MLM' contractees who buy the products /services (and not the general public) is because they have been led to believe that by doing so, and by recruiting others to do the same etc. ad infinitum, they will receive a future (unlimited) reward.

I've been examining the 'MLM' phenomenon for around 20 years. During this time, I've yet to find one so-called 'MLM' company which has voluntarily made key-information available to the public concerning the quantifiable results of its so-called 'income opportunity'.

The key-information which all 'MLM' bosses seek to hide concerns the overall number of persons who have signed contracts since the front companies were instigated and the retention rates of these contractees.

When rigorously investigated, the overall hidden net-loss churn rates for so-called 'MLM income opportunites' has turned out to have been effectively 100%. Thus, anyone claiming (or implying) that it is possible make a living in an 'MLM,' cannot be telling the truth and will not provide quantifiable evidence to back up his/her anecdotal claims.

Some of the biggest 'MLM' rackets (like 'Amway' and 'Herbalife') have hidden in plain sight and secretly churned tens of millions of losing participants over decades.